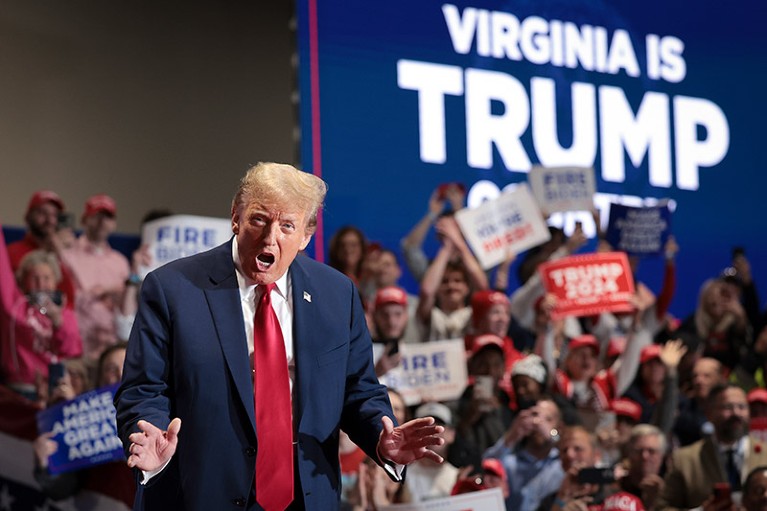

Former US president Donald Trump and current US President Joe Biden will face off in November to win a second term.Credit: Morry Gash, Jim Watson/AFP via Getty

Voters in 15 US states and one territory weighed in at the polls on 5 March, or ‘Super Tuesday’, and the results lock in a rematch between Republican Donald Trump and the incumbent, Democrat Joe Biden, in November’s election for the next US president. The outcome could have massive implications for the environment, public health and international collaborations between scientists — as well as, some fear, US democracy itself.

Has Biden followed the science? What researchers say

Trump soundly beat his lone remaining challenger for the Republican nomination, Nikki Haley, a former US ambassador to the United Nations, who dropped out of the race on 6 March. The former president prevailed despite facing 91 criminal charges alleging interference with the 2020 presidential election, economic fraud and mishandling of classified materials. The result of this year’s election could hinge on the outcome of those cases, as well as on potential long-shot presidential challenges from candidates labelling themselves as independents. But for now, Trump has consolidated his control over the Republican Party and will once again run against Biden, whom Democrats have rallied behind.

The two candidates have opposing views on a host of scientific issues. As president, Biden has promoted climate and clean-energy innovation, and bolstered scientific-integrity policies throughout the federal government that are meant to protect evidence-based decision-making. During his presidency from 2017–20, Trump repealed climate policies and promoted fossil fuels, while sidelining public-health officials and other government scientists. Each is expected to lean further into these stances if he wins a second term.

Here, Nature talks to policy analysts and researchers about what’s on the line in November.

Climate action or disruption?

Table of Contents

“It’s a trope to say that every election is critical, but this election is particularly stark in the two paths that it presents for the United States,” says Alexander Barron, an environmental scientist at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, who has worked under both Biden and former US president Barack Obama.

As president, Trump pulled the United States out of the Paris climate accord. He would probably do so again if elected while seeking to roll back climate regulations put in place by the Biden administration to curb greenhouse-gas emissions, including from vehicles and power plants. But there might be limits to what Trump would be able to achieve.

Trump at a campaign rally in Richmond, Virginia, on 2 March.Credit: Win McNamee/Getty

For instance, Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022, which by some estimates helped to lock in around US$1 trillion in funding for clean-energy programmes over a decade. If Trump wanted to repeal that legislation, it would require an act of Congress, which would be possible only if Republicans maintain control of the US House of Representatives and gain a majority in the Senate, which Democrats now control by a slim margin. And even then, observers say, the politics could be tricky given that large investments are already starting to flow into communities represented by lawmakers on both sides of the political aisle.

Nonetheless, Trump could still disrupt the climate agenda laid out in the IRA, says Greg Dotson, a legal scholar at the University of Oregon in Eugene, who was involved in crafting the legislation as a Democratic staff member in the Senate.

“The first Trump administration was very hostile to climate policies, and they didn’t feel necessarily restrained by the law,” Dotson says, noting that Trump could still block funding and rewrite climate-programme rules if he returned to office. By contrast, climate-policy specialists say that another four years under Biden could lock in nearly a decade of significant progress. This is what will be needed if the country is to have any hope of achieving Biden’s pledge to halve US emissions by 2030 and achieve net zero by mid-century.

“Getting to those targets is going to be a tremendous group effort,” Barron says. “We really need all levels of government and all sectors to continue moving in the right direction.”

The health of the nation

The two candidates also differ notably in their approach to investing in public health. For example, in each of Trump’s four years in office, his administration sought, unsuccessfully, to cut the budget of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), the country’s premier biomedical-research agency. Biden, on the other hand, kick-started the US$2.5-billion Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, aimed at tackling high-risk, high-reward biomedical research — which he’d probably continue to support if re-elected.

The Trump administration also attempted to cut funding for the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) — an agency tasked with protecting public health — and undermined its scientists during the COVID-19 pandemic by, for example, countering their claims about the seriousness of the health emergency. By contrast, Biden has proposed budget increases for the CDC and has publicly defended the agency and its scientists. “Trump did a lot to discredit public health and scientific agencies in the United States, and it has been difficult to rebuild the trust,” says Larry Levitt, an executive vice-president at the health-policy research organization KFF, based in San Francisco, California.

Biden has pledged to resecure the nationwide right to an abortion, once protected by a Supreme Court ruling in the case Roe v. Wade.Credit: Anna Moneymaker/Getty

That stance will probably continue. At a campaign rally last week, Trump hinted that he would endorse elements of the anti-vaccine movement if re-elected, suggesting that he would deny federal funds to schools with a vaccine mandate.

The United States’ role in global health is also at stake. During his presidency, Trump pulled the United States out of the World Health Organization (WHO) and generally pursued isolationist policies, Levitt says. “Biden has done a lot to undo that, but we will likely see a slip back if Trump were elected again,” he says. Officials in the Biden administration have expressed their commitment to a global pandemic treaty — an agreement being negotiated among countries to help prevent the next global-health emergency. Meanwhile, Republicans have been critical of it, suggesting that it could be a threat to US intellectual-property rights, forcing companies to share vaccine and treatment know-how.

Ever since the 2022 US Supreme Court decision that ended nationwide abortion rights, the issue has become crucial for voters. The two candidates have adopted opposing positions: Trump, who vowed to overturn abortion rights when he took office, now supports a national ban on abortions after 16 weeks of pregnancy, whereas Biden has vowed to once again secure abortion rights, by passing a law to protect them. Both pledges would require congressional action to be fulfilled, so it isn’t clear whether either would be successful. “We’re at one of the most consequential moments for abortion access in modern American history,” says Nourbese Flint, president of All Above All Action Fund, an abortion-justice advocacy group in Washington DC.

Cross-border science

Another area where Biden and Trump differ vastly is in their approach to immigration, as well as the visas that thousands of foreign students and scientists depend on to study and work in the United States. Weeks after Trump’s presidential inauguration, he introduced broad travel bans that stopped citizens from seven majority-Muslim countries, including Iran and Syria, from entering the United States. The move left international students stranded at airports and shocked the scientific community.

China Initiative’s shadow looms large for US scientists

When Biden took office in 2021, he quickly overturned the ban. And he has taken other steps to reform immigration for professionals such as scientists: in January 2022, the US Citizenship and Immigration Services clarified guidance for workers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) who are seeking visas to come to the United States. This has increased the number of STEM visas being issued, according to the agency.

Should either candidate win the election in November, these same stances will probably influence their agendas, experts say. But one area where their policies have more closely aligned — and is unlikely to change — is relations with China.

In 2018, under Trump, the US Department of Justice launched the China Initiative, a programme meant to safeguard US laboratories and businesses against espionage. The initiative led to a number of arrests of scientists with Chinese heritage, but when Biden took office, his administration reviewed the initiative and ended it, arguing that the programme had been perceived as using racial profiling to achieve its aims. Biden nonetheless continued with reforms introduced by Trump that required US universities and research organizations that were awarded more than $50 million per year in federal research funding to prove that they have instituted a research-security programme, including tougher scrutiny of foreign travel.

Such policies have made US institutions wary of collaborating with scientists in China, experts say. And in fact, studies have shown that scientific collaborations between the United States and China have continued to decrease under Biden. The number of students coming from China to study in the United States have dropped, too.

Trump’s presidential push renews fears for US science

At the end of last year, Republican lawmakers in the US House of Representatives wrote that it had been “unwise” of the Biden administration to end the China Initiative, sparking fear among civil-liberties advocates that they would try to reinstate the programme. They hope that a renewed Biden administration would stave off such efforts, but aren’t sure what would happen under a second Trump term.

“Relations with China won’t improve in the foreseeable future, but they could get worse,” says Jenny Lee, a higher-education researcher and vice-president for international affairs at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

The elections in November will undoubtedly affect government policies on many scientific issues. But for Barron, similar to many others, science is just one of many concerns that he has about a potential second term for Trump, who has questioned the legitimacy of the 2020 election, promoted misinformation on a number of fronts, and signalled that he will institute new rules that critics argue will make it easier to fire career government employees who oppose his politics. “I would put myself in the camp that is most worried about democracy,” Barron says.