As environmental, social and humanitarian crises escalate, the world can no longer afford two things: first, the costs of economic inequality; and second, the rich. Between 2020 and 2022, the world’s most affluent 1% of people captured nearly twice as much of the new global wealth created as did the other 99% of individuals put together1, and in 2019 they emitted as much carbon dioxide as the poorest two-thirds of humanity2. In the decade to 2022, the world’s billionaires more than doubled their wealth, to almost US$12 trillion.

The evidence gathered by social epidemiologists, including us, shows that large differences in income are a powerful social stressor that is increasingly rendering societies dysfunctional. For example, bigger gaps between rich and poor are accompanied by higher rates of homicide and imprisonment. They also correspond to more infant mortality, obesity, drug abuse and COVID-19 deaths, as well as higher rates of teenage pregnancy and lower levels of child well-being, social mobility and public trust3,4. The homicide rate in the United States — the most unequal Western democracy — is more than 11 times that in Norway (see go.nature.com/49fuujr). Imprisonment rates are ten times as high, and infant mortality and obesity rates twice as high.

Reducing inequality benefits everyone — so why isn’t it happening?

These problems don’t just hit the poorest individuals, although the poorest are most badly affected. Even affluent people would enjoy a better quality of life if they lived in a country with a more equal distribution of wealth, similar to a Scandinavian nation. They might see improvements in their mental health and have a reduced chance of becoming victims of violence; their children might do better at school and be less likely to take dangerous drugs.

The costs of inequality are also excruciatingly high for governments. For example, the Equality Trust, a charity based in London (of which we are patrons and co-founders), estimated that the United Kingdom alone could save more than £100 billion ($126 billion) per year if it reduced its inequalities to the average of those in the five countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that have the smallest income differentials — Denmark, Finland, Belgium, Norway and the Netherlands5. And that is considering just four areas: greater number of years lived in full health, better mental health, reduced homicide rates and lower imprisonment rates.

Many commentators have drawn attention to the environmental need to limit economic growth and instead prioritize sustainability and well-being6,7. Here we argue that tackling inequality is the foremost task of that transformation. Greater equality will reduce unhealthy and excess consumption, and will increase the solidarity and cohesion that are needed to make societies more adaptable in the face of climate and other emergencies.

Social anxieties drive stress

Table of Contents

The underlying reasons for inequality having such profound and wide-ranging impacts are psychosocial. By accentuating differences in status and social class — for example, through the type of car someone drives, their clothing or where they live — inequality increases feelings of superiority and of inferiority. The view that some people are worth more than others can undermine people’s confidence and feelings of self-worth8. And, as studies of cortisol responses show, worry about how others see us is a powerful stressor9.

People queue for food parcels in Lagos, Nigeria.Credit: Temilade Adelaja/Reuters

Rates of ‘status anxiety’ have been found to be increased in all income groups in more-unequal societies10. Chronic stress has well-documented effects on mortality — it can double death rates11. Health-related behaviours are also affected by stress. Diet, exercise and smoking all show social gradients, but people are least likely to adopt healthy lifestyles when they feel stressed.

Violence and bullying are also linked to competition for social status. Aggression is frequently triggered by disrespect, humiliation and loss of face. Bullying among schoolchildren is around six times as common in more-unequal countries12. In the United States, homicide rates were five times as high in states with higher levels of inequality as in those with a more even distribution of wealth13.

Status compels consumption

Inequality also increases consumerism. Perceived links between wealth and self-worth drive people to buy goods associated with high social status and thus enhance how they appear to others — as US economist Thorstein Veblen set out more than a century ago in his book The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899). Studies show that people who live in more-unequal societies spend more on status goods14.

Our work has shown that the amount spent on advertising as a proportion of gross domestic product is higher in countries with greater inequality. The well-publicized lifestyles of the rich promote standards and ways of living that others seek to emulate, triggering cascades of expenditure for holiday homes, swimming pools, travel, clothes and expensive cars.

The ‘Bill Gates problem’: do billionaire philanthropists skew global health research?

Oxfam reports that, on average, each of the richest 1% of people in the world produces 100 times the emissions of the average person in the poorest half of the world’s population15. That is the scale of the injustice. As poorer countries raise their material standards, the rich will have to lower theirs.

Inequality also makes it harder to implement environmental policies. Changes are resisted if people feel that the burden is not being shared fairly. For example, in 2018, the gilets jaunes (yellow vests) protests erupted across France in response to President Emmanuel Macron’s attempt to implement an ‘eco-tax’ on fuel by adding a few percentage points to pump prices. The proposed tax was seen widely as unfair — particularly for the rural poor, for whom diesel and petrol are necessities. By 2019, the government had dropped the idea. Similarly, Brazilian truck drivers protested against rises in fuel tax in 2018, disrupting roads and supply chains.

Do unequal societies perform worse when it comes to the environment, then? Yes. For rich, developed countries for which data were available, we found a strong correlation between levels of equality and a score on an index we created of performance in five environmental areas: air pollution; recycling of waste materials; the carbon emissions of the rich; progress towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals; and international cooperation (UN treaties ratified and avoidance of unilateral coercive measures).

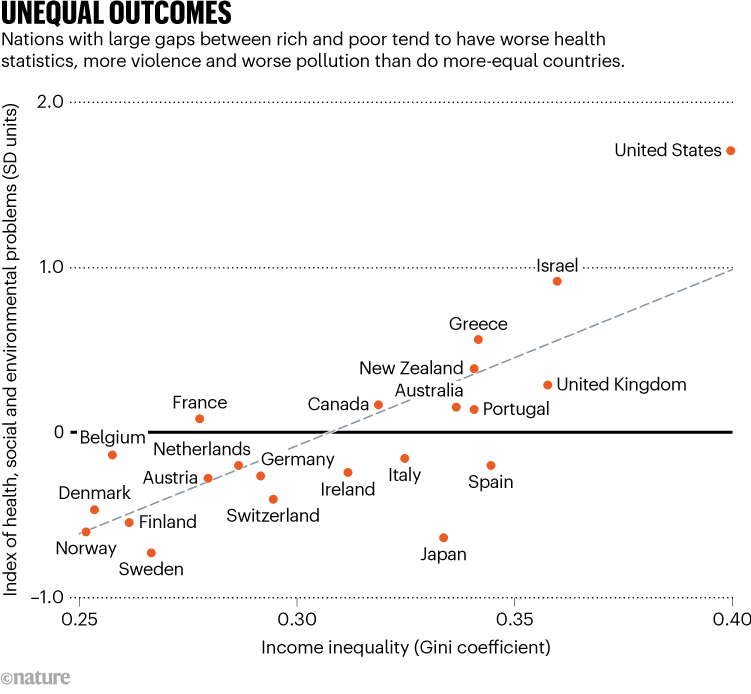

That correlation clearly holds when social and health problems are also factored in (see ‘Unequal outcomes’). To show this, we combined our environmental performance index with another that we developed previously that considers ten health and social problems: infant mortality, life expectancy, mental illness, obesity, educational attainment, teenage births, homicides, imprisonment, social mobility and trust. There’s a clear trend, with more-unequal societies having worse scores.

Source: Analysis by R. G. Wilkinson & K. E. Pickett

Other studies have also shown that more-equal societies are more cohesive, with higher levels of trust and participation in local groups16. And, compared with less-equal rich countries, another 10–20% of the populations of more-equal countries think that environmental protection should be prioritized over economic growth17. More-equal societies also perform better on the Global Peace Index (which ranks states on their levels of peacefulness), and provide more foreign aid. The UN target is for countries to spend 0.7% of their gross national income (GNI) on foreign aid; Sweden and Norway each give around 1% of their GNI, whereas the United Kingdom gives 0.5% and the United States only 0.2%.

Policymakers must act

The scientific evidence is stark that reducing inequality is a fundamental precondition for addressing the environmental, health and social crises the world is facing. It’s essential that policymakers act quickly to reverse decades of rising inequality and curb the highest incomes.

First, governments should choose progressive forms of taxation, which shift economic burdens from people with low incomes to those with high earnings, to reduce inequality and to pay for the infrastructure that the world needs to transition to carbon neutrality and sustainability. Although governments might baulk at this suggestion, there’s plenty of headroom. For example, tax rates on the highest incomes in the United States were well above 70% for about half of the twentieth century — much higher than today’s top rate of 37%. To shore up public support, governments need to make a strong case that the whole of society should contribute to funding the clean energy transition and good health.

To build a better world, stop chasing economic growth

International agreements to close tax havens and loopholes must be made. Corporate tax avoidance is estimated to cost poor countries $100 billion per year — enough to educate an extra 124 million children and prevent perhaps 8 million maternal and infant deaths annually. OECD member countries are responsible for more than two-thirds of these tax losses, according to the Tax Justice Network, an advocacy group in Bristol, UK. The OECD estimates that low- or middle-income countries lose three times as much to tax havens as they receive in foreign aid.

Although not yet tried, the merits of a consumption tax — calculated on the basis of personal income minus savings — to restrain consumption should also be considered. Unlike value-added and sales taxes, such a tax could be made very progressive. Bans on advertising tobacco, alcohol, gambling and prescription drugs are common internationally, but taxes to restrict advertising more generally would help to reduce consumption. Energy costs might also be made progressive by charging more per unit at higher levels of consumption.

Legislation and incentives will also be needed to ensure that large companies — which dominate the global economy — are run more fairly. For example, business practices such as employee ownership, representation on company boards and share ownership, as well as mutuals and cooperatives, tend to reduce the scale of income and wealth inequality. In contrast to the 200:1 ratio reported by one analyst for the top to the bottom pay rates among the 100 largest-worth companies listed on the FTSE 100 stock-market index (see go.nature.com/3p9cdbv), the Mondragon group of Spanish cooperatives has an agreed maximum ratio of 9:1. And such companies perform well in ethical and sustainability terms. The Mondragon group came 11th in Fortune magazine’s 2020 ‘Change the World’ list, which recognizes companies for implementing innovative business strategies with a positive global impact.

Reducing economic inequality is not a panacea for health, social and environmental problems, but it is central to solving them all. Greater equality confers the same benefits on a society however it is achieved. Countries that adopt multifaceted approaches will go furthest and fastest.