Of the many young people whom Cathy Eng has treated for cancer, the person who stood out the most was a young woman with a 65-year-old’s disease. The 16-year-old had flown from China to Texas to receive treatment for a gastrointestinal cancer that typically occurs in older adults. Her parents had sold their house to fund her care, but it was already too late. “She had such advanced disease, there was not much that I could do,” says Eng, now an oncologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Eng specializes in adult cancers. And although the teenager, who she saw about a decade ago, was Eng’s youngest patient, she was hardly the only one to seem too young and healthy for the kind of cancer that she had.

Thousands of miles away, in Mumbai, India, surgeon George Barreto had been noticing the same thing. The observations quickly became personal, he says. Friends and family members were also developing improbable forms of cancer. “And then I made a mistake people should never do,” says Barreto, now at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia. “I promised them I would get to the bottom of this.”

Almost half of cancer deaths are preventable

It took years to make headway on that promise, as oncologists such as Barreto and Eng gathered hard data. Statistics from around the world are now clear: the rates of more than a dozen cancers are increasing among adults under the age of 50. This rise varies from country to country and cancer to cancer, but models based on global data predict that the number of early-onset cancer cases will increase by around 30% between 2019 and 20301. In the United States, colorectal cancer — which typically strikes men in their mid-60s or older — has become the leading cause of cancer death among men under 502. In young women, it has become the second leading cause of cancer death.

As calls mount for better screening, awareness and treatments, investigators are scrambling to explain why rates are increasing. The most likely contributors — such as rising rates of obesity and early-cancer screening — do not fully account for the increase. Some are searching for answers in the gut microbiome or in the genomes of tumours themselves. But many think that the answers are still buried in studies that have tracked the lives and health of children born half a century ago. “If it had been a single smoking gun, our studies would have at least pointed to one factor,” says Sonia Kupfer, a gastroenterologist at the University of Chicago in Illinois. “But it doesn’t seem to be that — it seems to be a combination of many different factors.”

On the increase

Table of Contents

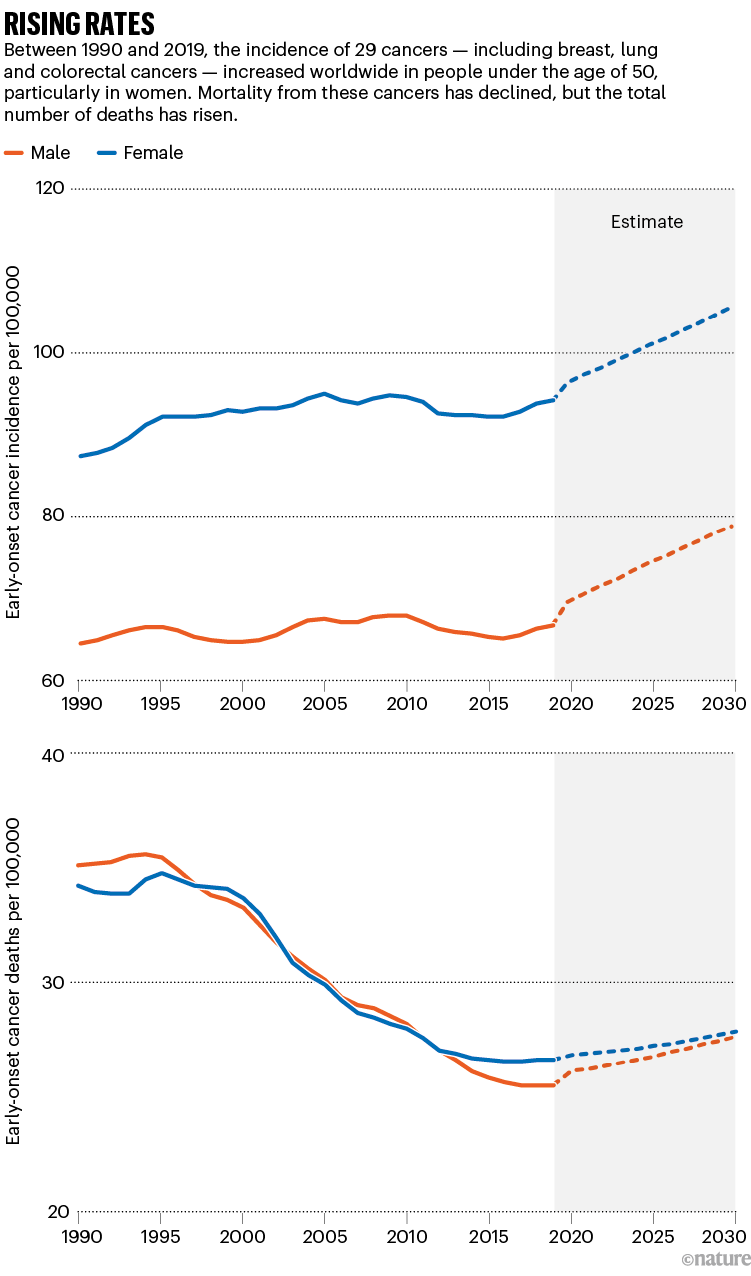

In some countries, including the United States, deaths owing to cancer are declining thanks to increased screening, decreasing rates of smoking and new treatment options. Globally, however, cancer is on the rise (see ‘Rising rates’). Early-onset cancers — often defined as those that occur in adults under the age of 50 — still account for only a fraction of the total cases, but the incidence rate has been growing. This rise, coupled with an increase in global population, means that the number of deaths from early-onset cancers has risen by nearly 28% between 1990 and 2019 worldwide. Models also suggest that mortality could climb1.

Source: Ref. 1

Often, these early-onset cancers affect the digestive system, with some of the sharpest increases in rates of colorectal, pancreatic and stomach cancer. Globally, colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers and tends to draw the most attention. But others — including breast and prostate cancers — are also on the rise.

In the United States, where data on cancer incidence is particularly rigorous, uterine cancer has increased by 2% each year since the mid-1990s among adults younger than 502. Early-onset breast cancer increased by 3.8% per year between 2016 and 20193.

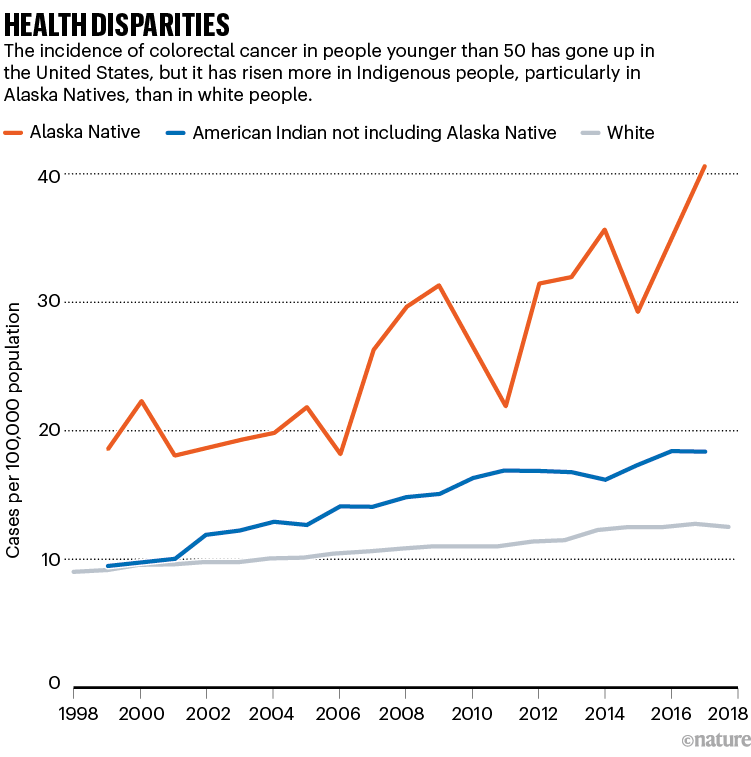

The rate of cancer among young adults in the United States has increased faster in women than in men, and in Hispanic people faster than in non-Hispanic white people. Colorectal cancer rates in young people are rising faster in American Indian and Alaska Native people than they are in white people (see ‘Health disparities’). And Black people with early onset colorectal cancer are more likely to be diagnosed younger and at a more advanced stage than are white people. “It is likely that social determinants of health are playing a role in early-onset cancer disparities,” says Kupfer. Such determinants include access to healthy foods, lifestyle factors and systemic racism.

Source: Ref. 4

Cancer’s shift to younger demographics has driven a push for earlier screening. Advocates have been promoting events targeted at the under 50s. And high-profile cases — such as the 2020 death of actor Chadwick Boseman from colon cancer at the age of 43 — have helped to raise awareness. In 2018, the American Cancer Society urged people to be screened for colorectal cancer starting at age 45, rather than the previous recommendation of 50.

In Alaska, health leaders serving Alaska Native people have been recommending even earlier screening — at age 40 — since 2013. But the barriers to screening are high; many communities are inaccessible by road, and some people have to charter a plane to reach a facility in which they can have a colonoscopy. “If the weather’s bad, you could be there a week,” says Diana Redwood, an epidemiologist at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium in Anchorage.

These efforts have paid off to some extent: screening rates in the community have more than doubled over the past three decades, and now exceed those of state residents who are not Alaska Natives. But mortality from colorectal cancer has not budged, says Redwood. Although colorectal cancer rates are falling in people over 50 years old, the age group that is still most likely to be screened, the rates in younger Alaska Native people are climbing by 5.2% each year4.

Genetic clues

The prominence of gastrointestinal cancers and the coincidence with dietary changes in many countries point to the rising rates of obesity and diets rich in processed foods as likely culprits in contributing to rising case rates. But statistical analyses suggest that these factors are not enough to explain the full picture, says Daniel Huang, a hepatologist at the National University of Singapore. “Many have hypothesized that things like obesity and alcohol consumption might explain some of our findings,” he says. “But it looks like you need a deeper dive into the data.”

Those analyses match the anecdotal experiences that clinicians described to Nature: often, the young people they treat were fit and seemingly healthy, with few cancer risk factors. One 32-year-old woman that Eng treated was preparing for a marathon. Previous physicians had dismissed the blood in her stool as irritable bowel syndrome caused by intense training. “She was healthy as can be,” says Eng. “If you looked at her, you would have no idea that more than half of her liver was tumour.”

US cancer deaths are falling — but not fast enough

Prominent cancer-research funders, including the US National Cancer Institute and Cancer Research UK, have supported programmes to find other contributors to early-onset cancer. One approach has been to look for genetic clues in early-onset tumours that might set them apart from tumours in older adults. Pathologist Shuji Ogino at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues have found some possible characteristics of aggressive tumours in early-onset cancers. For example, aggressive tumours are sometimes particularly adept at suppressing the body’s immune responses to cancer, and Ogino’s team has found signs of a muted immune response to some early-onset tumours5.

But these differences are subtle, he says, and researchers have yet to find a clear demarcation between early-onset and later-onset cancers. “It’s not dichotomous, but more like a continuum,” he says.

Researchers have also looked at the microorganisms that reside in the human body. Disruptions in microbiome composition, such as those caused by dietary changes or antibiotics, have been linked to inflammation and increased risk of several diseases, including some forms of cancer. Whether there is a link between the microbiome and early-onset cancers is still in question: results so far are still preliminary and it’s difficult to gather long-term data, says Christopher Lieu, an oncologist at the University of Colorado Cancer Center in Aurora. “The list of things that impact the microbiome is so extensive,” he says. “You’re asking people to recall what they ate as kids, and I can barely remember what I ate for breakfast.”

Looking to the past

But increasing the size of studies could help. Eng is developing a project to look at possible correlations between microbiome composition and the onset of cancer at a young age, and she plans to combine her data with those from collaborators in Africa, Europe and South America. Because the number of early-onset cancer cases is still relatively small at any one centre, this kind of international coordination is important to give statistical analyses more power, says Kimmie Ng, founding director of the Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer Center at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

Another approach is to scrutinize the differences between countries. For example, Japan and South Korea are located near one another and are similar economically. But early-onset colorectal cancer is increasing at a faster rate in South Korea than it is in Japan, says Tomotaka Ugai, a cancer epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School. Ugai and his collaborators hope to determine why.

How gut microbes are joining the fight against cancer

But data are scarce in some countries. In South Africa, cancer data are collected only from the 16% of the population that has medical insurance, says Boitumelo Ramasodi, regional director for Southern Africa at the Global Colon Cancer Association, a non-profit organization in Washington DC. Those who do not have insurance are not counted. And families rarely keep records of who has died of cancer, she says. For many Black people in the country, cancer is considered a white person’s disease; Ramasodi initially struggled to make sense of her own diagnosis of colorectal cancer at the age of 44. “Black people don’t get cancer,” she thought at the time. “I’m young, I’m Black, why do I have cancer?”

Ultimately, researchers will also have to look back in time for clues to understand rising early-onset cancers, says epidemiologist Barbara Cohn at the Public Health Institute in Oakland, California. Research has shown that cancers can arise many years after an exposure to a carcinogen, such as asbestos or cigarette smoke. “If the latent period is decades, then where do you look?” she says. “We believe that you need to look as early as possible in life to understand this.”

To do that, researchers will need 40–60 years of data, collected from thousands of people — enough to capture a sufficient number of early-onset cancers. Cohn directs an unusual repository of data and blood samples that have been collected from about 20,000 expectant mothers during pregnancy since 1959. Researchers have followed many of the original participants, and their children, since then.

Cohn and Caitlin Murphy, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, have already tried combing through the data to look for ties to early-onset cancers, and have found a possible association between early colorectal cancer and prenatal exposure to a particular synthetic form of progesterone, sometimes taken to prevent premature labour6. But the study must be repeated in other cohorts for investigators to be sure.

More informed

Finding studies that follow cohorts from the prenatal stage to adulthood is a challenge. The ideal study would enrol thousands of expectant mothers in several countries, collect data and samples of blood, saliva and urine, and then track them for decades, says Ogino. A team funded by Cancer Research UK, the US National Cancer Institute and others will analyse data from the United States, Mexico and several European countries, to look for environmental exposures and other possible influences on early-onset cancer risk. Murphy and Cohn also hope to incorporate data collected from fathers and are working with collaborators to analyse blood samples in search of more chemicals that offspring might have encountered in the womb.

Murphy expects the results to be complicated. “At first, I really believed that there was something unique about early-onset colorectal cancers compared to older adults, and a risk factor out there that explains everything,” she says. “The more time I’ve spent, the more it seems clear that there’s not just one particular thing, it’s a bunch of risk factors.”

Cruel fusion: What a young man’s death means for childhood cancer

For now, it’s important for physicians to share their data on early-onset cancers and to follow their patients even after they complete their therapy, to learn more about how best to treat them, says Irit Ben-Aharon, an oncologist at the Rambam Health Care Campus in Haifa, Israel. Cancer treatment in young people can be fraught: some cancer drugs can cause cardiovascular problems or even secondary cancers years after treatment — a risk that becomes more concerning in a young person, she says.

Young adults might also be pregnant at the time of diagnosis, or more concerned about the impact of cancer drugs on their fertility than are people who are past their reproductive years. And they are less likely to be retired, and more likely to be concerned about whether their cancer treatment will cause long-term cognitive damage that could hinder their ability to work.

When Candace Henley was diagnosed with colorectal cancer at the age of 35, she was a single mother raising five children. The aggressive surgery she received rendered her unable to continue in her job as a bus driver, and the family was soon homeless. “I didn’t know what questions to ask and so the decisions around treatment were made for me,” says Henley, who went on to found The Blue Hat Foundation for Colorectal Cancer Awareness in Chicago, Illinois. “No one unfortunately considered what my needs were at home.”

In the years since Eng first noticed how young her patients were, certain things have changed. Some advocacy groups have begun targeting their information campaigns at younger audiences. People with early-onset cancers are more informed now and seek out second opinions when physicians dismiss their symptoms, Eng says. This could mean that physicians will more often catch early-onset cancers before they have spread and become more difficult to treat.

But Barreto still doesn’t have all the answers he promised. He wants to study the impact of prenatal stresses, such as exposure to alcohol and cigarette smoke or malnourishment, on early-cancer risk. He’s contacted scientists around the world, but no biobanking projects contain the data and samples that he requires.

If all of the data he and others need aren’t available now, it’s understandable, he says. “We never saw this coming. But in 20 years if we don’t have databases to record this, it’s our failure. It’s negligence.”