Last November, a clinical trial offered a glimmer of hope in the often gloomy fight against antimicrobial resistance. An oral antibiotic, called zoliflodacin, was shown to be effective against the bacterium that causes the sexually transmitted disease gonorrhoea. And because it is the first of a new class of antibiotics, the drug also offers hope of stopping the spread of ‘super gonorrhoea’,which is resistant to most standard treatments.

That month brought good news on another front, too. An international research team reported that a new antifungal drug, fosravuconazole, was safe and effective at treating a devastating disease called fungal mycetoma, which scars and damages the skin and can lead to amputation if left untreated. Antifungal drugs are difficult to develop and are scarce. The only existing mycetoma treatment requires taking expensive pills for a long time: two pills per dose, twice per day, for several months. The new drug requires only taking two pills once a week, which could reduce stress and expense for tens of thousands of people in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

What is especially notable about the success of these two drugs, however, is that they followed a new path to get this far. Both trials were conducted by non-profit organizations that were founded specifically to bring new drugs to the market: zoliflodacin by the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP) based in Geneva, Switzerland, and fosravuconazole by the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi), also based in Geneva.

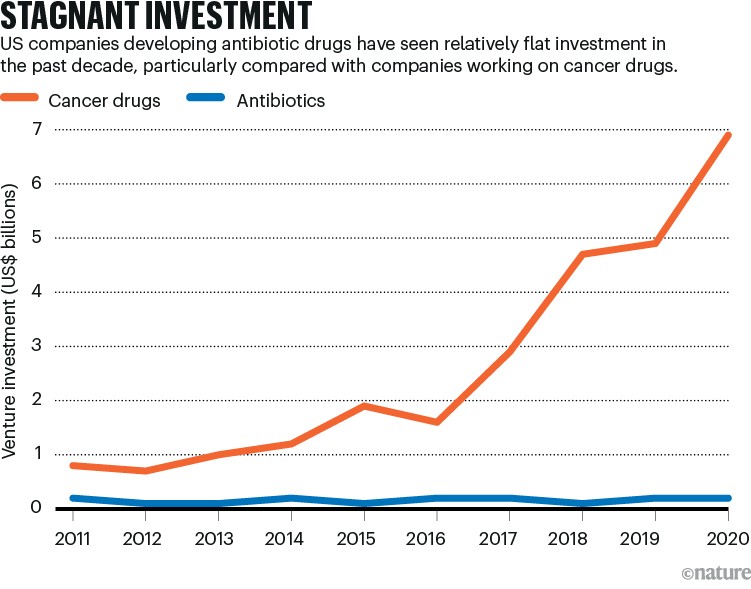

These organizations hope to fill a big gap in the development and testing of drugs at a time when most legacy pharmaceutical firms have withdrawn from antimicrobial drug discovery, and many of the small biotechnology companies that picked up the torch have gone bankrupt (see ‘Stagnant investment’). These two latest achievements suggest that non-profits could help to solve the problem of drug access, while fending off the rise of drug-resistant microbes, which contribute to almost five million deaths per year.

Source: D. Thomas & C. Wessel The State of Innovation in Antibacterial Therapeutics (BIO, 2022)

“For someone like me, a clinician on the front lines, this is good news,” says Helen Boucher, an infectious-diseases physician and dean of the Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, Massachusetts, who has testified before the US Congress about the challenge of finding such drugs. “We need more antibiotics, and we need to exploit all the different routes available to develop them.”

Pass-along value

Table of Contents

Both drugs followed a complicated path to the market. They were originally developed by conventional pharmaceutical companies: fosravuconazole by Eisai in Tokyo, and zoliflodacin by Entasis Therapeutics in Waltham, Massachusetts, which is now part of Innoviva in Burlingame, California. Under the agreements these companies have with the non-profit organizations, the original firms retain some rights to the drugs, either for manufacturing and distribution or for sales in some high-income countries. But the goal has been to get both of these drugs to low-income countries at affordable prices.

For the antifungal, fosravuconazole, that is already happening. On the basis of the trial results reported last year, Sudan’s Ministry of Health has allowed people to receive the drug while the country’s National Medicines and Poisons Board evaluates its registration. The trial, which recruited 104 people in Sudan between 2017 and 2020, compared treatment using fosravuconazole over 12 months with the standard of care, a drug called itraconazole (see go.nature.com/3t635ro). The trial found no statistically significant clinical difference, meaning that treatment for mycetoma could be made in a less expensive and less complex way.

“Most of the itraconazole that is available in the African endemic countries is very expensive; it can cost over US$2,000 per year,” says Borna Nyaoke-Anoke, a Nairobi-based physician and head of the DNDi’s mycetoma disease programme, who managed the trial. “We’re looking at a neglected tropical disease affecting the most vulnerable and neglected patients, who are barely able to make $1 a day.”

Eisai first developed ravuconazole, the predecessor to fosravuconazole, as part of a search for treatments for skin infections. But in 2003, a Venezuelan research project found that the drug was effective in mice against Chagas disease1, a parasitic infection that affects several million people in Latin America. The study caught the attention of the DNDi, which was searching for treatments to address the neglected disease at the time. Eisai and the DNDi jointly launched a phase II trial in Bolivia to explore the drug’s efficacy against Chagas disease. Although it was unsuccessful, an unrelated research project at the Mycetoma Research Center at the University of Khartoum in Sudan found that ravuconazole was effective against fungal mycetoma2.

The antibiotic paradox: why companies can’t afford to create life-saving drugs

This offered the compound a second chance at approval, and validated a strategy that the DNDi has pursued since 2003, when the organization was founded by members of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, also known as Doctors Without Borders): breathing life into drugs that have been abandoned or underused. “We call it repurposing: taking a drug that was developed for one indication, that was sort of left on the shelf for whatever reason, that we then repurpose for another indication,” says Rachel Cohen, the DNDi’s senior adviser for global policy advocacy and access. (The organization has since developed its own drug discovery programme, but it does not operate laboratories or manufacturing facilities.)

The development of zoliflodacin was bumpier; its route to market encapsulates the decline of antibiotics research. The compound was first identified at Pharmacia, a pharmaceutical company based in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Pharmacia was acquired by Pfizer, based in New York City, in 2003. When Pfizer exited antibiotics research in 2011, zoliflodacin went to AstraZeneca, a drug firm in Cambridge, UK. Then, when AstraZeneca began to withdraw from antibiotic research, the drug ended up at the newly founded Entasis in 2015. Then the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded a clinical phase II trial, which tested the safety and efficacy of zoliflodacin in 179 people3. Entasis also managed to acquire an agreement from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that will earn it regulatory approval once the company has completed one successful phase III trial. The FDA typically requires two such trials before granting approval.

During this time, the incidence of gonorrhoea was rising around the world3; in the United States, it increased by two-thirds between 2013 and 2017. And the bacterium was steadily gaining resistance to the several families of antibiotics used to cure it, turning what had been an easily handled infection into an almost untreatable menace.

The World Health Organization (WHO) was also turning its attention to the problem of antibiotic resistance; it proposed a global action plan that was adopted in 2015. The following year, the WHO helped to create the GARDP. Funded with €2 million (US$2.16 million) from several governments and MSF, the GARDP started with administrative support from the DNDi and followed its model of identifying low-cost opportunities to spin off useful drugs.

“DNDi is set up to focus on neglected diseases, and we were set up to address antimicrobial resistance,” says microbiologist Laura Piddock, who is the GARDP’s scientific director. In 2019, the GARDP became an independent organization with a focus on specific bacterial infections in low-income nations that lack full access to new drugs.

At around the same time, Entasis decided to focus its limited funding on a different drug from its AstraZeneca programme, a new combination antibiotic aimed at drug-resistant pneumonia. “We were a small biotech at the time, and our focus was the US and Europe,” says John Mueller, who was one of Entasis’s founders and is now chief development officer at Innoviva Specialty Therapeutics, a subsidiary of Innoviva. (Innoviva bought Entasis in 2022.) “GARDP’s interest was low- and middle-income countries, and those usually are later down in your commercialization path,” Mueller adds. Innoviva licensed zoliflodacin to the GARDP, and agreed to collaborate with the non-profit organization on the phase III trial — which expanded to 16 sites in 5 countries — and the subsequent FDA registration.

Push and pull

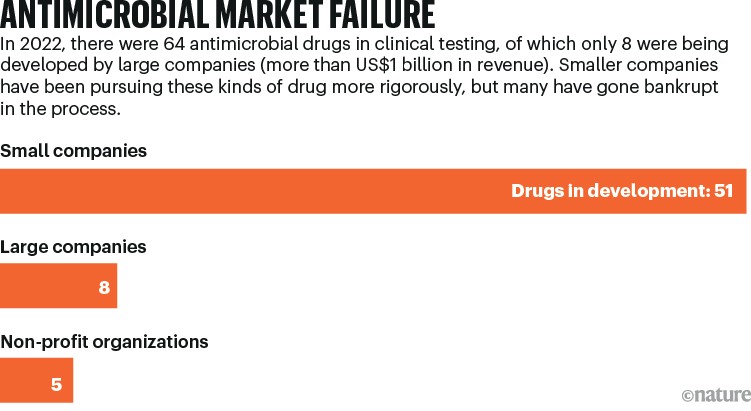

As large pharmaceutical companies continue to back out of the antibiotics business, drug developers have been trying to stimulate public conversation about creating better incentives for small biotechnology firms (see ‘Antimicrobial market failure’). There are two basic strategies: push and pull. Push incentives support research by getting new compounds through trials and up to the point of approval; pull incentives take over afterwards, supporting companies so that they can survive until their earnings start to flow. Push incentives have had some success. The best known example is the non-profit organization CARB-X (Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator), based at Boston University, which has committed US$452 million to early-stage research, contributed by governments and big philanthropic organizations.

Source: D. Thomas & C. Wessel The State of Innovation in Antibacterial Therapeutics (BIO, 2022)

Pull incentives, however, have faced political headwinds. Although many options have been debated, only one has launched: a subscription-style arrangement in which drug companies receive grants that constitute advance down payments on future sales. The idea is that by removing the incentive for a company to sell a new drug aggressively, and thereby reducing the use of the drug, it will delay the inevitable arrival of resistance to it. Only one entity has committed to that subscription programme so far: the UK government. In 2022, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) decreed that the National Health Service (NHS) could justify paying £10 million (US$12.6 million) per year to two companies for future purchases of two drugs that will be used against severely drug-resistant, hospital-acquired infections. In mid-2023, the NHS endorsed the concept and announced plans to expand it, potentially raising the payments to £20 million. By contrast, in the United States, a piece of legislation known as the PASTEUR Act, which would create a similar programme, has not made it through Congress despite repeated tries.

But, by funding the registration and launch of drugs in countries that cannot afford to pay commercial prices for them, both the DNDi and the GARDP are effectively providing pull incentives — which is something that these organizations can afford to do because, as non-profits with external funders, they do not need to earn the level of income that a company would require. That means they are providing a model not only for how much-needed drugs can be rescued in the development process, but also for how companies can be supported when their compounds are released onto the market.

Specialists who have been watching this field for a while say that it’s important not to forget the part that pharmaceutical companies have played in developing fosravuconazole and zoliflodacin, which both emerged from conventional discovery programmes. Drug discovery is extremely expensive; one estimate from 2016 calculates the cost from the initial identification of a compound through to FDA approval at $1.4 billion. Although the DNDi and the GARDP have each gathered millions of dollars from funders, neither has had to bear that kind of bill. That makes the non-profits “a crucial add-on”, says Kevin Outterson, the executive director of CARB-X. “What GARDP and DNDi do is unique in the world and absolutely necessary,” he adds. But, he says, they’re “not a replacement”.