Symptoms of measles include an itchy rash of red-brown spots.Credit: Jim Goodson/CDC/Science Photo Library

UK health services are battling an outbreak of measles — causing alarm in a nation that had eliminated the disease in 2017.

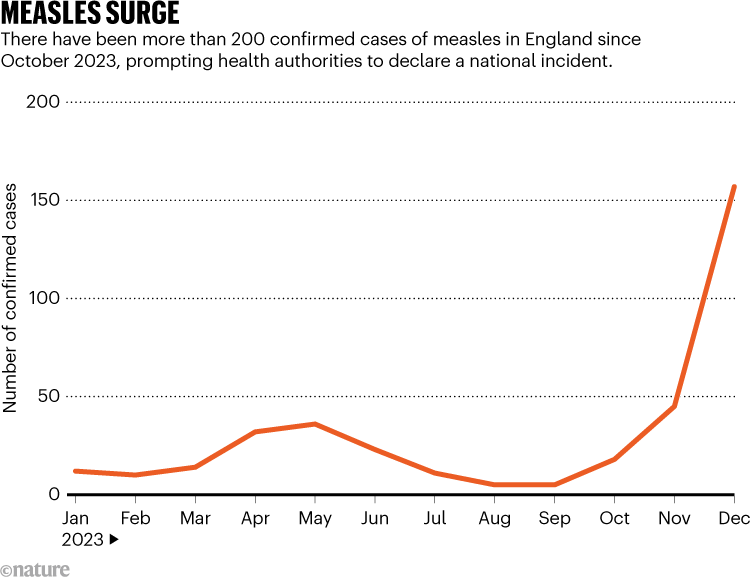

On 19 January, the UK Health and Security Agency (UKHSA), the public-health authority, declared a national incident over rising cases of measles. The agency has logged more than 200 cases since 1 October 2023 (see ‘Measles surge’).

A decline in uptake of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine, which is given in two doses, during the COVID-19 pandemic has spurred the spread of the disease across England and Europe, while small outbreaks have occurred in a handful of US states.

Measles is caused by a virus and is highly contagious. It is spread through coughing and sneezing. Symptoms include a fever, runny nose and an itchy rash of red-brown spots. “It’s considered to be one of the most infectious respiratory infections there is,” says population health researcher Helen Bedford at University College London. Those most at risk include babies, young children, pregnant women and those with a weakened immune system.

Nature explores the uptick in cases.

Why are measles cases rising in the UK?

Table of Contents

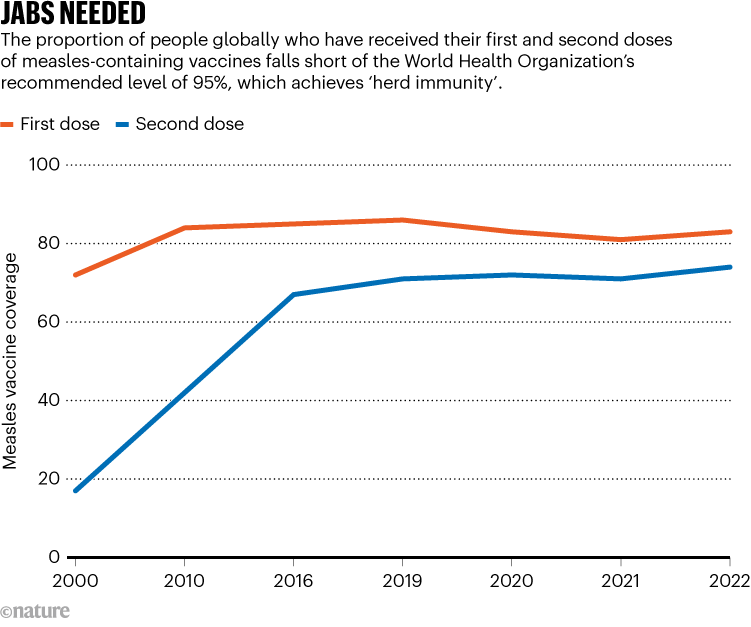

Low uptake of the measles vaccine is a key driver of the UK measles cases, say researchers. Around 85% of children in England had received two MMR vaccine doses by five years old, according to data from the National Health Service (NHS). This falls below the vaccination rate of at least 95% needed to achieve ‘herd immunity’ — which substantially reduces disease spread — and is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO; see ‘Jabs needed’).

Source: UK government

“It is worrying but not all that surprising to see another measles outbreak within the UK,” paediatrician Ronny Cheung at the Evelina London Children’s Hospital said in a statement to the UK Science Media Centre. “The fact remains that vaccination coverage for children under the age of 5 is now the lowest it has ever been in the past 10 years,” he said.

The COVID-19 pandemic worsened matters, says Bedford. During the pandemic, measles cases dipped because of social-distancing measures. But vaccine uptake also dropped, contributing to the latest surge in cases, she says.

Moreover, the pandemic might have caused people to question vaccine safety, which might have delayed uptake, says Bedford. “People have got more questions, which, unfortunately, due to cuts in public health funding, aren’t always properly addressed,” she says.

How is the UK tackling the surge?

On 22 January, the NHS launched a vaccination campaign, urging millions of parents and carers to book vaccine appointments for their children. Health services will contact all parents of unvaccinated children aged 6 to 11. “If parents and young people respond to the information, and the message to get vaccinated, we could stop it in its tracks,” says Bedford.

Vaccination rates are lowest in London, where just 74% of children have received two doses of the vaccine. Two doses are 97% effective against catching measles. One local council in the capital has launched a vaccine awareness campaign in multiple languages to reach more people.

Without further action, the outbreak could spread more widely across the United Kingdom, causing deaths, says Bedford.

When was the last time there was a spike in UK cases?

In 2018, a measles outbreak of around 900 cases occurred in England. That followed the WHO’s declaration in 2017 that the United Kingdom had eliminated the disease, defined as the absence of circulating measles.

In response to the outbreak, Public Health England, UKHSA’s predecessor, advised people to get the MMR vaccine. “The only thing that you can do to stop measles spreading is get vaccinated,” says Bedford. “This means catching up people who didn’t have it, including those who didn’t have it 20 years ago,” she says.

What’s happening elsewhere?

In recent weeks in the United States, there have been 23 confirmed measles cases across Georgia, Missouri, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Many of the cases were linked to international travellers returning to the country, and reflect a rise in measles cases globally, according to a newsletter sent by the US Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention (CDC) on 25 January. There were 56 reported US cases last year, down from 121 in 2022, says the newsletter. This is much less than the more than 1,200 US infections in 2019.

But Europe is facing a more alarming situation. There was a 45-fold rise in measles cases in the WHO’s European region from 2022 to 2023. In 2023, the region’s 40 member states reported some 42,200 measles cases, up from less than 1,000 cases in 2022.

The rise in cases is also the result of declining national vaccination rates, which fell from 92%, on average, in 2019 to 91% in 2022, according to the WHO.

Globally in 2022, measles cases increased by 18%, and deaths from measles increased by 43%, compared with 2021, according to a WHO report released last November.