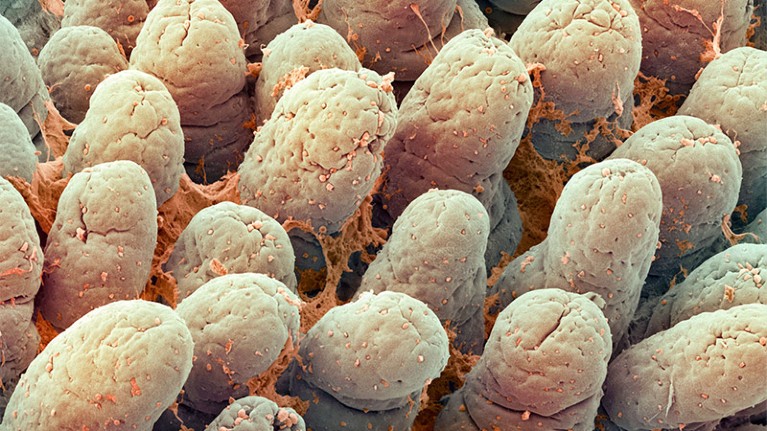

The lining of the small intestine contains finger-like structures that help to absorb nutrients and fluid.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library via Alamy

Mental stress has long been linked to flare-ups of gastrointestinal conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Now, researchers have uncovered exact details of one way that stress can harm the intestines — by setting off a biochemical cascade that reshapes the gut microbiome.

Their study, published today in Cell Metabolism1, is nice, says Christoph Thaiss, a microbiologist and neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, because it highlights how the brain — despite being far away from the gastrointestinal tract — can still influence it.

Metabolism malfunction

Table of Contents

IBS, which causes abdominal pain and diarrhoea, affects one in ten people. Up to ten million people worldwide have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which causes inflammation of the intestines and triggers similar symptoms. Study co-author Xiao Zheng, a metabolism researcher at the China Pharmaceutical University in Nanjing, wanted to understand what happens on the cellular level to trigger these conditions.

To find out, he and his colleagues exposed mice to chronic stress for two weeks and observed the effects. The animals ended up with reduced levels of cells that help to protect the intestines from pathogens, compared with mice that weren’t stressed. This is because the metabolism of intestinal stem cells that normally transform into these protector cells was malfunctioning.

Chronic stress can inflame the gut — now scientists know why

Seeking a reason, the researchers turned to the animals’ microbiomes — the collection of bacteria and other microbes in their guts that aid digestion. Previous work2 had shown that the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the body’s ‘fight or flight’ response and often triggered by mental stress, can reshape the microbiome. Some bacteria of the genus Lactobacillus, which naturally occur in the gut and proliferate under stressful conditions, produce a chemical called indole-3-acetate (IAA). The researchers found that a raised level of IAA, triggered by stress, was preventing the mouse intestinal stem cells from becoming protector cells.

Although this study was conducted in mice, the researchers gathered evidence that their findings might hold true for humans: the team found elevated levels of both Lactobacillus bacteria and IAA in the faeces of people with depression, compared with that of people without it. “When we suffer from stress, our gut microbiome is also suffering from stress,” Zheng says.

The authors also found a possible antidote, in mice at least. When they gave stressed mice a supplement called α-ketoglutarate, which is taken by some bodybuilders, it kick-started the metabolism of the impaired stem cells in their intestines. Thaiss warns that more work is needed to understand the long-term effects of the supplement and whether it reduces the symptoms of gut dysfunction.

A piece of the puzzle

Because stress triggers a raft of biochemical changes in the body, this study alone won’t tell the whole story of the stress–gut connection, Thaiss adds. In a paper published in Cell last year3, he and his colleagues uncovered a separate biochemical pathway that begins with a stressed brain sending a signal and ends with immune cells in the gut becoming overactive. How these mechanisms interact, if at all, is unclear.

Thaiss also says that the IAA study tackled only the downstream effects of stress on the gut — more work is needed to understand how the brain transmits signals that kick off the bacterial proliferation. Zheng says he and his colleagues plan to investigate these upstream effects next, in addition to further testing the safety and efficacy of α-ketoglutarate.

The IAA study “is certainly a new piece of the puzzle”, says Gerard Clarke, a neurogastroenterologist at University College Cork in Ireland, “but how many pieces are in that puzzle is still an open question”.