Last year, around two-thirds of Pakistan was affected by widespread flash flooding, with more than 1,500 people killed and around 33 million made homeless. Almost 2,000 people died in flash floods across Africa, and parts of the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman and Yemen were inundated with water.

Flash floods are a growing threat in some of the world’s driest regions. Deluges can trigger sudden and rapid torrents of run-off that flow down dry river beds and rocky channels.

Because parched soils repel water rather than allowing it to soak in, flash floods can be more devastating in drylands than in wetter areas. Surges can result from relatively small amounts of rain, as little as 10 millimetres in one hour. By comparison, floods in wetter regions typically follow more prolonged bouts of rainfall.

Rapid run-off also erodes soils, adding sediment and debris to the water. The dangers are greatest in mountainous areas, where water can gush suddenly through gullies and down slopes. For example, a flash flood last year in Datong town in Qinghai province, China, washed away more than 1,500 homes in less than one hour.

Yet residents of drylands are underprepared for flash floods, compared with people in the tropics. In dry areas, where drought is a big concern, settlements tend to be near rivers or on floodplains. Dams and levees are low priorities.

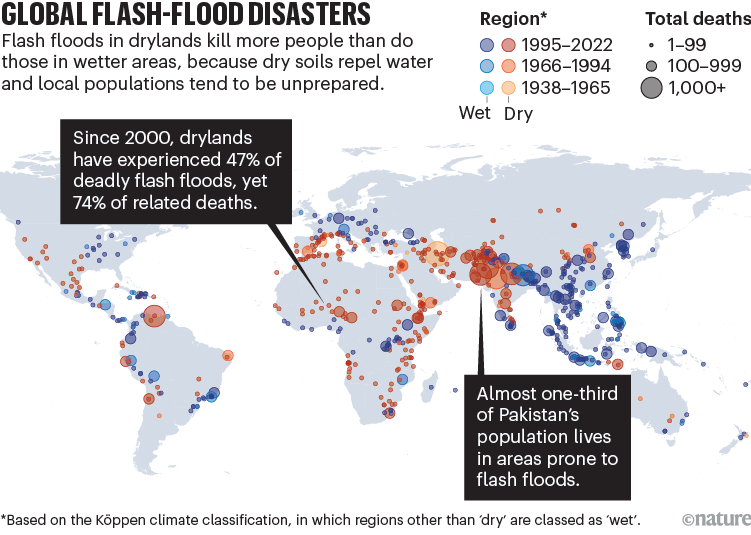

Dryland residents are paying a high price. Our analysis using the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT; www.emdat.be) shows that, since 2000, such regions experienced less than half (47%) of deadly flash floods globally, yet saw almost three-quarters (74%) of related deaths (see ‘Global flash-flood disasters’). The majority of these floods (87%) and associated deaths (97%) occurred in low- and middle-income countries.

Source: EM-DAT, CRED/UC Louvain (www.emdat.be); Analysis by J. Yin et al.

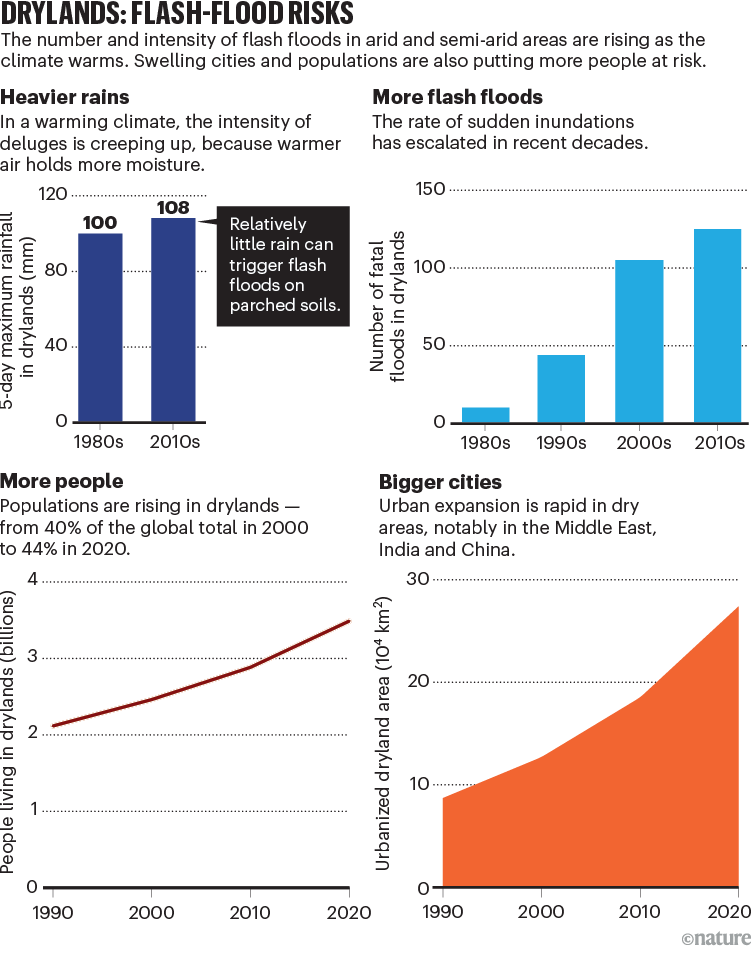

A slew of other factors will put many more people at risk from flash floods in future (see ‘Drylands: flash-flood risks’). Climate change is making such events more intense and frequent1–3. In parts of Pakistan, for example, the 5-day maximum level of rainfall is 75% greater today than it was before 1900 (see go.nature.com/41awzzj). Our analysis shows that globally, the rate of dryland flash flooding was 20 times higher between 2000 and 2022 than it was between 1900 and 1999 (numbering 278 and 64 floods, respectively).

More people are living in drylands — from 40% of the global population in 2000 to 44% in 2020, by our calculation. Such regions will host 51% of the world’s population growth by 2025, with half of those people living in low-income countries, and only 1% in developed ones4. Cities are expanding rapidly in areas such as the Middle East, India and China5. And the proportion of the world’s land area classed as arid or semi-arid is projected to increase as the world warms — from 41% in 2000 to 48% by 20254.

Pakistan is one of the most exposed nations. Almost one-third of the country’s population (72 million of 230 million people) lives in high-risk flash-flood zones. As ever, vulnerable groups such as older people, women and children experience the worst effects.

Researchers, practitioners and policymakers need to model, assess and mitigate the risk of flash flooding in drylands in a changing environment. Here, we set out six research priorities for doing so.

Source: EM-DAT, CRED/UC Louvain (www.emdat.be); Analysis by J. Yin et al.

Gather data and map the risks

Table of Contents

Assessing the likelihood and consequences of flash floods requires a lot of data. These include: meteorological and hydrological measurements; topographic data and digital elevation models; records of assets and previous losses; and census data. However, most dryland regions lack much of this information, because national governments often don’t recognize its value and many lack the resources to gather it.

Researchers, international organizations and non-governmental organizations need to help such countries to update their flood-risk information. Initiatives include the Global Flood Partnership run by the European Union (https://gfp.jrc.ec.europa.eu), which is developing flood observation and modelling infrastructure in low- to middle-income countries such as Myanmar. Governments should map flash-flood risks and distribute them online (as the United Kingdom does; see go.nature.com/3xt9hfz) to pinpoint locations that are prone to flooding, restrict construction and target flood-protection measures.

Flood risk needs to be carefully communicated, because it can exacerbate inequalities. In drylands, low-income and minority populations tend to live in flood-prone areas such as riversides6. If maps show these areas to be high risk, they could be deprived of local infrastructure investment, increasing their vulnerability. Socio-economic data should therefore also be conveyed to decision makers alongside the maps.

Develop early-warning systems

Early-warning systems for flash floods are operating in some wealthy countries, including the United States and in EU nations. For example, the US system (FLASH) forecasts surface water flows at 10-minute intervals and with a spatial resolution of 1 kilometre. These forecasts combine real-time observations from radar, satellites and sensors with hydrological models, and can provide a few hours’ notice of flash floods. If preparation and response plans are also in place, that might give enough time for governments to allocate rescue resources and for residents to protect homes and move to safety points. However, few low- and middle-income nations have these systems, because they lack the data and models to support them, as well as political incentives and funding.

How climate change and unplanned urban sprawl bring more landslides

To rectify this, the World Meteorological Organization is running a programme to provide weather forecasters and disaster-management agencies with real-time information around flash-flood threats (see go.nature.com/3xsw4fg). So far, 28 warning systems are up and running, with another 39 in development. Eight of the operational systems are in drylands, together with ten of those still in development. More dryland nations need to be engaged.

Forecasting of flash floods in drylands will need tailoring to local contexts, including soil types, terrains and sediment loads. Where data are scarce, uncertainties and limits need to be better understood. Use of wireless sensors and alternative sources of local data, such as use of social media and crowdsourcing, need to be explored.

Boost resilience to sudden floods

Dams, barriers and dikes will need to be installed in drylands to protect settlements. For example, China has been building thousands of kilometres of levees along the main stream and tributaries of the Yellow River. This is expensive, however, involving hundreds of projects with costs ranging from millions to billions of dollars.

Researchers need to examine the trade-offs. For example, protection measures might encourage more development in flood-prone areas — as was the case in Columbia, South Carolina, which experienced extensive damage from a flash flood in 2015. And dams and levees built to hold back small floods could offer a false sense of security from rare, extreme inundations7, including one that flooded the Atacama region in South America in 2015. Failure of one protection element, such as a reservoir, can send flood waters cascading downstream, as was narrowly averted at California’s Oroville Dam in 2017. The environmental impacts need to be understood, such as those resulting from stopping the silt and sediment that fertilize the floodplain.

Vehicles cross a bridge over the Yolo Bypass in Sacramento, California, where weirs divert flood waters away from houses onto floodplains.Credit: Fred Greaves/Reuters

Nature-based solutions are cheaper. For example, in Pakistan, the government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province has restored almost 350,000 hectares of forests in its ‘Billion Tree Tsunami’ planting drive. In the Yolo Bypass project in Sacramento, California, levees are being replaced with weirs to divert flood waters away from houses and onto natural floodplains. Large residential areas should adopt ‘sponge city’ techniques that reduce run-off, such as permeable pavements, green roofs, rainwater harvesting and swales (ditches). These are being installed in cities throughout China, including Xining in Qinghai province, the largest city on the Tibetan Plateau.

Researchers should aim to quantify how effective natural features are at storing and conveying water, and how resilient they are to extreme floods. Local differences in soil and vegetation conditions must be considered. More needs to be known about how the systems degrade and how to maintain them. Promising projects include the World Bank’s Global Program on Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Resilience and the Sindh Resilience Project in Pakistan, as well as government-led water and soil conservation initiatives in the Loess Plateau in north-central China.

Land-use regulations need to be tightened, such as by preventing informal development in floodplains. Flood-protection standards for buildings need to be improved. For example, the International Residential Code, used as the basis of many national and local guidelines, requires the lowest floors of buildings to be 30 centimetres above the average level of a ‘once a century’ flood. Such levels no longer reflect flood probability in a warming world.

Plan for long-term resettlement

In flood-prone areas, governments should develop plans for temporary and even permanent resettlement. Elevated roads, evacuation routes and emergency shelters must be designed, such as those used in Indonesia for tsunamis and in the United States for hurricanes. In the longer term, as climate-change impacts accelerate, managed retreat might be required8. For example, the Chinese government has relocated more than 600,000 people from flash-flood zones in the arid mountains of southern Shaanxi province over the past decade.

Managed resettlement is more equitable and efficient than leaving people to fend for themselves. Cross-disciplinary research in social science, geography, engineering and psychology is required to investigate the best way to manage retreat, by providing essential services and assistance while avoiding food insecurity and lost livelihoods.

Provide finance beyond disaster aid

Risk-transfer schemes — such as flood insurance, catastrophe bonds and solidarity funds — should be developed for drylands. For example, China is developing a national system of flood insurance products. These have been incorporated into the national emergency-management system and launched in dozens of pilot cities, including Zhengzhou in Henan province. Such products include weather index insurance, which offers compensation for loss of crops and livestock when rainfall exceeds a certain threshold. Catastrophe insurance protects businesses and residences against extreme events that are too expensive for insurers to cover, such as super typhoons or floods that occur only once in 1,000 years.

Five ways to ensure flood-risk research helps the most vulnerable

Algeria has made catastrophe insurance mandatory. Every insurance company there must join its national Catastrophe Risk Insurance Pool to cover disaster losses in proportion to their market share. All properties must be insured, with premiums set by the government.

Researchers need to study the impacts of such schemes, especially on equity. For example, vulnerable families living in flood-prone zones might not be able to afford high premiums9. Around 50% of losses in wealthy countries are covered by insurance, but there is less than 10% coverage in many poorer countries. For example, claims for Hurricane Sandy in the United States in 2012 covered 50% of the damages. By contrast, after a record-breaking flash flood in China’s Henan province in July 2021, flood insurance claims exceeded US$1.7 billion — only 11% of the total losses.

Partnerships between countries — such as China’s ‘Belt and Road’ project and the ‘Build Back Better World’ initiative proposed by the G7 group of advanced economies — should be sought to establish solidarity funds that can share the risk of large disasters, as the EU has done. The United Nations climate ‘loss and damage’ fund, approved last year at the COP27 summit in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, should be leveraged to finance long-term flood-risk reduction in drylands, once mechanisms are formulated.

Improve public awareness and responses

People who live in drylands need to be more aware of flash-flood risks. Policymakers should offer guidance to help residents to adapt their behaviours and take precautionary measures — such as by installing flood-protection structures, knowing evacuation routes and warning signals, identifying areas prone to flooding or landslides, and avoiding walking or driving through flooded areas and standing water.

Researchers need to explore how best to communicate the effectiveness of measures, and how perceptions of risk influence responses to flash floods10. Social factors need to be explored — such as age, gender, education, income, ownership, culture, religion and political context. For example, past experience is important for recognizing risks and adapting behaviours. But, for rare events, memories fade and only catastrophes are remembered for a long time.

Collective behaviours also need to be understood11. Social-media messages can provide rapid information about locations, impacts and responses to dryland floods, as revealed through data mining and artificial intelligence. Models can integrate complex human behaviour into quantitative risk assessments, to improve management strategies. Given that flood risks are evolving, it is important to adapt policies as information becomes available. Interdisciplinary analysis will also be needed to evaluate the robustness of flood-resilience strategies for a range of risks and future scenarios12.

Before more lives are lost, let’s offer dryland residents the means to assure their safety.