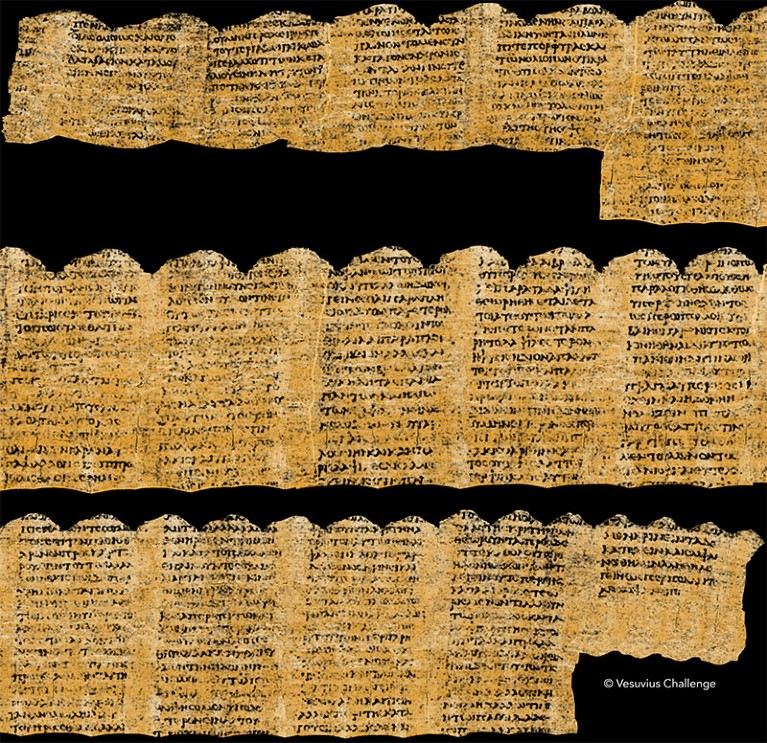

Text from the Herculaneum scroll, which has been unseen for 2,000 years.Credit: Vesuvius Challenge

A team of student researchers has made a giant contribution to solving one of the biggest mysteries in archaeology by revealing the content of Greek writing inside a charred scroll buried 2,000 years ago by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The winners of a contest called the Vesuvius Challenge trained their machine-learning algorithms on scans of the rolled-up papyrus, unveiling a previously unknown philosophical work that discusses senses and pleasure. The feat paves the way for artificial intelligence (AI) techniques to soon decipher the rest of the scrolls in their entirety, which researchers say could have revolutionary implications for our understanding of the ancient world.

The achievement has ignited the usually slow-moving world of ancient studies. It’s “what I always thought was a pipe dream coming true”, says Kenneth Lapatin, curator of antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California, who was not involved in the contest. The newly revealed text discusses sources of pleasure including music, the taste of capers and the colour purple. “It’s an historic moment,” says classicist Bob Fowler at Bristol University, UK, one of the prize judges. The three students, from Egypt, Switzerland and the United States, who revealed the text share a US$700,000 grand prize.

The scroll is one of hundreds of intact papyri excavated in the 18th century from a luxury Roman villa in Herculaneum, Italy. These lumps of carbonized ash — known as the Herculaneum scrolls — are the only library that survives from the ancient world, but are too fragile to open.

The winning entry, announced on 5 February, reveals hundreds of words across more than 15 columns of text, corresponding to around 5% of an entire scroll. “The contest has cleared the air on all the people saying will this even work,” says Brent Seales, a computer scientist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and co-founder of the prize. “Nobody doubts that anymore.”

20-year mission

Table of Contents

In the centuries after the scrolls were discovered, many people have attempted to open some of them, destroying some and leaving others in pieces. Papyrologists are still working to decipher and stitch back together the resulting, horribly fragmented, texts. But the chunks in the worst condition — the most hopeless cases, adding up to perhaps 280 entire scrolls — were left intact. They’re held mostly in the National Library of Naples, Italy, with a few in Paris, London and Oxford, UK.

The Herculaneum scroll was burnt and buried by an eruption of Mount Vesuvius.Credit: Vesuvius Challenge

Seales has been trying to read these concealed texts for nearly 20 years. His team developed software to “virtually unwrap” the surfaces of rolled-up papyri using three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) images. In 2019, he carried two of the scrolls from the Institut de France in Paris to the Diamond Light Source particle accelerator near Oxford to make high-resolution scans.

Mapping the surfaces was time consuming, however, and the carbon-based ink used to write the scrolls has the same density as papyrus in CT scans, so it was impossible to differentiate in imaging. Seales and his colleagues wondered whether machine-learning models might be trained to unwrap the scrolls and distinguish the ink. But making sense of all the data was a gigantic task for his small team.

Seales was approached by Silicon Valley entrepreneur Nat Friedman, who had become intrigued by the Herculaneum scrolls after watching a talk by Seales online. Friedman suggested opening the challenge to contestants. He donated $125,000 to launch the effort and raised hundreds of thousands more on Twitter, and Seales released his software along with the high-resolution scans. They launched the Vesuvius Challenge in March 2023, setting a grand prize for reading four passages, of at least 140 characters each, before the end of the year.

Key to the contest’s success was its “blend of competition and cooperation”, says Friedman. Smaller prizes were awarded along the way to incentivize progress, with the winning code released at each stage to “level up” the community so contestants could build on each other’s advances.

The colour purple

A key innovation came over the summer, when US entrepreneur and former physicist Casey Handmer noticed a faint texture in the scans, like cracked mud — he called it “crackle” — that seemed to form the shapes of Greek letters. Luke Farritor, an undergraduate studying computer science at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, used the crackle to train a machine-learning algorithm, revealing the word porphyras, “purple”, which won him the prize for revealing the first letters in late October. An Egyptian PhD student in Berlin, Youssef Nader , who followed with even clearer images of the text, came second.

A team of researchers used machine-learning to image the shapes of ink on the rolled-up scroll.Credit: Vesuvius Challenge

Their code was released with less than three months for contestants to scale up their reads before the deadline for the final prize of 31 December. “We were biting our nails,” says Friedman. But in the final week they received 18 submissions. A technical jury checked entrants’ code, then passed twelve submissions to a committee of papyrologists who transcribed the text and assessed each entry for legibility. Only one fully met the prize criteria: a team formed by Farritor and Nader, along with Julian Schilliger, a Swiss robotics student at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

The results are “incredible”, says judge Federica Nicolardi, a papyrologist at the University of Naples Federico II. “We were all completely amazed by the images they were showing.” She and her colleagues are now racing to analyse fully the text that has been revealed.

Music, pleasure and capers

The content of most of the previously opened Herculaneum scrolls relates to the Epicurean school of philosophy, and seems to have formed the working library of a follower of the Athenian philosopher Epicurus named Philodemus. The new text doesn’t name the author but from a rough first read, say Fowler and Nicolardi, it is probably also by Philodemus. As well as pleasurable tastes and sights, it includes a figure called Xenophantus, possibly a flute-player of that name mentioned by the ancient authors Seneca and Plutarch, whose evocative playing apparently caused Alexander the Great to reach for his weapons.

Lapatin says the topics discussed by Philodemus, and his predecessor Epicurus, are still relevant today. “The basic questions Epicurus was asking are the ones that face us all as humans. How do we live a good life? How do we avoid pain?” But “the real gains are still ahead of us,” he says. “What’s so exciting to me is less what this scroll says, but that the decipherment of this scroll bodes well for the decipherment of the hundreds of scrolls that we had previously given up on.”

There is likely to be more Greek philosophy in the scrolls: “I’d love it if he had some works by Aristotle,” says papyrologist and prize judge Richard Janko at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Meanwhile some of the opened scrolls, written in Latin, cover a broader subject area, raising the possibility of lost poetry and literature by writers from Homer to Sappho. The scrolls “will yield who knows what kinds of new secrets”, says Fowler. “We’re all very excited.”

The achievement is also likely to fuel debate over whether further investigations should be conducted at the Herculaneum villa, entire levels of which have never been excavated. Janko and Fowler are convinced the villa’s main library was never found, and that thousands more scrolls could still be underground. More broadly, the machine learning techniques pioneered by Seales and the Vesuvius Challenge contestants could now be used to study other types of hidden text, such as “cartonnage”, recycled papyri often used to wrap Egyptian mummies.

The next step is to decipher one entire work. Friedman has announced a new set of Vesuvius Challenge prizes for 2024, with the aim of reading 85% of a scroll by the end of the year. But in the meantime, just getting this far “feels like a miracle”, he says. “I can’t believe it worked.”