Illustration by Fabrizio Lenci

When Manuel Chevalier met Mine Altinli in Montpellier, France, both were in their late twenties. Chevalier was wrapping up his doctoral thesis on southern Africa’s past climates, whereas Altinli had just embarked on a PhD on how infections develop. Both were excited about a career in academia. “I expected to be a postdoc for five to six years after my PhD, hopping from country to country. I felt happy about that prospect,” says Chevalier.

Today, the couple are renting a flat in Hamburg, Germany, where Altinli researches mosquito-borne viruses as a postdoc at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine. Chevalier is finishing a postdoc at the University of Bonn, some 5 hours away by train, although he works remotely. Both still enjoy their science. But both are now 35, and after eight years of postdocs in three countries for Chevalier, the impermanence of their lives has begun to chafe.

If they’d had stable jobs, they would probably have bought a home by now, they say. The uncertainty grows more frustrating over time, says Altinli. “I know I’m good. I’m working hard. And still I’m not sure if it will be enough to yield a permanent job in academia.” Country-hopping no longer charms Chevalier. “We have one big move left. We won’t move any more for postdocs,” he says.

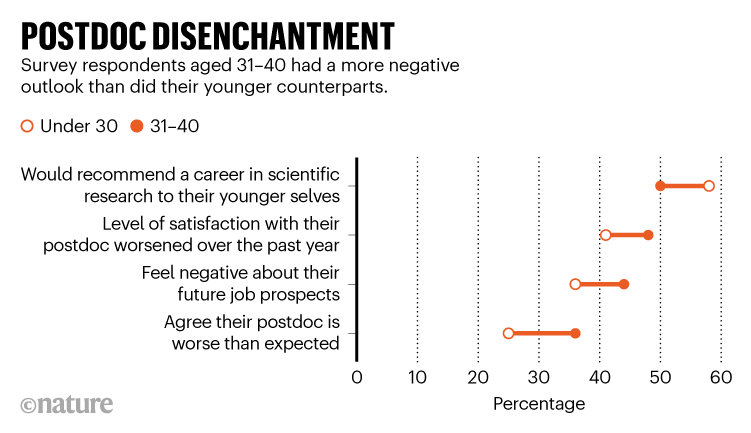

Their sentiments fit a trend that shines through in Nature’s second global survey of postdoctoral researchers: postdocs in their thirties are less happy in their careers, overall, than their peers who are in their twenties (see ‘Postdoc disenchantment’). Postdocs aged 31–40 were more negative about job prospects, job security and work–life balance than were those under 30. They were also more likely to report mental-health challenges.

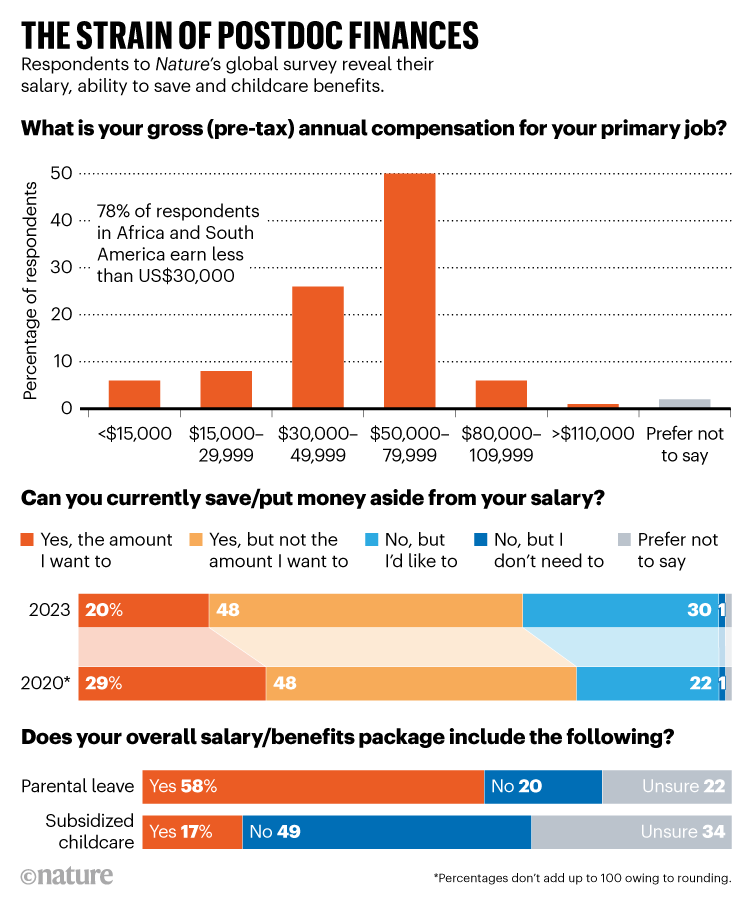

Postdocs aged 31–40 surveyed by Nature are more likely to have completed their first short-term contract since their PhD, and career dissatisfaction is higher among those on their third or fourth postdoc (34%) than for those on their first (24%). Many in this age group also find that their changing priorities and personal goals at this stage in their lives place them on course for a head-on collision with a postdoc’s long hours and low pay (see ‘The strain of postdoc finances’ for a glimpse of how respondents of all ages reported their salaries, savings and benefits).

“Postdoc life often coincides with life stages where there is a desire to settle more permanently and [there are] increasing family responsibilities, either involving elderly parents or young children,” says Emma Williams, an academic careers coach based in Cambridge, UK.

Life on hold

Not meeting these expectations and milestones weighs on postdocs as they get older, says Faredin Alejevski, a neuroscientist in his late thirties and a postdoc at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. He says he is expected to sacrifice evenings and weekends, and to neglect his social life and holidays, all for a career that offers no guarantees. The short-term nature of postdoc contracts prevents him and others from settling down and starting a family, he says. “We feel that we are falling behind in life.”

When Nature discussed the survey findings with postdocs in their thirties around the world, many said that they perceive growing dissatisfaction, both in their own lives and in their academic communities.

Archaeologist Petra Heřmánková says there is an emotional cost to the impermanence of postdoc life.Credit: Martina Caskova

“I totally see myself in Nature’s data,” says Petra Heřmánková, a Czech archaeologist based at Aarhus University in Denmark. Like Chevalier and Altinli, she has moved a lot for work: she did her PhD in Prague, then a postdoc in Sydney, Australia, followed by a second postdoc in Denmark. This August, she started a three-year assistant professor position at Aarhus. Although she says it “looks fancier” than a postdoc, the chances of progressing to a permanent job are no greater. When the appointment ends, she will be 40.

Postdocs are organizing to obtain better pay and working conditions — that can only be a good thing

There is an emotional cost to existing in a state of impermanence, Heřmánková says — simple things, such as not being able to accumulate belongings, start to weigh heavily after a while. “When I left Australia, I only took two suitcases and one backpack. I haven’t had a TV since 2015,” she says. She has not been able to buy a house, and with rising property prices both in Denmark and in the Czech Republic outpacing salaries, she is uncertain if she ever will. However, she and her Czech husband did have a baby earlier this year. “I was waiting for more permanency and stability” before starting a family, says Heřmánková. When she realized they were not materializing, “we decided to just go for it”.

“There’s a huge difference between being in your twenties and being in your thirties,” says 32-year-old Marc Van Goethem, a South African bioinformatician who started his postdoc journey in 2018 at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, California. Life as a junior postdoc was great, he recalls. “I was publishing great stuff and enjoyed living in America.” Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, and health reasons led to a move back to South Africa, where his wife became pregnant with their first child.

Marc Van Goethem is a postdoc in Saudi Arabia but his family remains in South Africa.Credit: Marc W. Van Goethem

But postdoc salaries across Africa are low — in Nature’s survey, 60% of postdocs there reported earning less than US$15,000 per year — so Van Goethem secured his current postdoc at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia. The pay is significantly more than he would earn back home, and his employer subsidizes his living expenses and transport costs, meaning he can comfortably support his wife and child who remain in South Africa. “I guess I’m kind of hacking the system for now,” he says. But the future is uncertain. Moving back to South Africa — even to a permanent academic position — would mean a drastic pay cut. And being apart from his family takes an emotional toll. “Doing science is still so rewarding. But the personal costs are many. It’s like eating caviar off a paper plate,” he says.

Postdoc career optimism rebounds after COVID in global Nature survey

Ingrid Alvial, an ecologist doing a postdoc at the Catholic University of Maule in Talca, Chile, also sees herself represented in Nature’s data. “In your thirties or forties, family takes an important meaning in our lives and priorities change as you search for a stable job opportunity,” she says. She’s 42 and had her first baby this year — having delayed motherhood like many highly educated women in Chile, she says. Becoming a mother has increased her “mental load”, she says, and also means she now needs a stable job.

Rei Yamashita, who studies marine pollution and seabird ecology at the University of Tokyo, is also in her forties, and she says she felt more pessimistic about her career at 39 than at 30. She’s been a postdoc for the past 15 years and has made significant sacrifices for her career, such as not buying a house or becoming a parent, and yet she remains without a permanent position.

Coping mechanisms

When work and life collide, something has to give. Some researchers put off having children until they are through the postdoc phase, such as Shehryar Khan, a materials-science postdoctoral fellow in his early thirties at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. He and his wife have decided to hold off on starting a family until Khan’s fellowship ends in two years’ time. By then, he hopes to have found a position as a principal investigator (PI) back in Canada, where he did his PhD.

They both want children, Khan says, but in the current economic environment, they cannot afford for his wife to take time off work to care for a child. That puts the couple at odds with their South Asian values that dictate having children soon after marriage. “We are extremely saddened by not being able to start our family,” he says, but adds that he thinks such decisions are becoming more common among all postdocs.

In countries where paid parental leave and subsidized childcare are the norm, starting a family can be easier. Even so, becoming a parent changes the way postdocs structure and think about their work (see ‘The struggle to be a postdoc and a parent simultaneously’).

Juliette Kamp, a 33-year-old psychiatry postdoc at the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, welcomed her first child, a daughter, at the end of 2022. Work used to be a big, perhaps her biggest, priority. Now her wife and daughter come first. Both Kamp and her wife — their child’s birth mother and a physician training to be a rheumatologist — were able to take paid parental leave and afford four days of childcare a week. Thanks to state subsidy, the cost comes to €1,000 (US$1,050) a month, a sum that won’t break the bank.

Still, there are challenges. They live in Leiden, and the hour-long commute to Kamp’s workplace in Rotterdam is not ideal because she has to cut her workdays short to pick up her daughter on time. But having found a coveted place at a childcare centre in Leiden trumps that. Fear of losing that childcare has also dampened Kamp’s willingness to move abroad for work, even though it could be beneficial for her career. For Kamp, the trade-off is worth it to be settled in her family life: there’s “more happiness” since her daughter arrived.

Psychiatry postdoc Juliette Kamp now puts her wife and daughter above work priorities.Credit: Anniek Meesters

The availability of paid parental leave and subsidized childcare is still patchy, according to Nature’s survey data. Those who say their salary or benefits package includes subsidized childcare are still firmly in the minority, although the proportion has increased from 14% in 2020 to 17% this year. Paid parental leave is available to 58% of postdocs surveyed, again slightly up from 53% in 2020, but this year, a greater share of male respondents said they were not able to access it (25%) than did in 2020 (21%).

Desperately seeking stability

According to Nature’s data, 17% of postdocs aged 31–40 wish that they had known about the need to explore other career paths before setting off on their postdoc journey, compared with 12% of postdocs aged under 30.

Chevalier says he was warned during his PhD that the academic job market would be tough. He’s about to embark on another postdoc, which thankfully won’t require him to move, and Altinli is on the lookout for a permanent job. She would prefer academia but isn’t ruling out an industry post. They have agreed that where they settle will be determined by which of them gets a permanent job first.

Both Heřmánková and Alvial speak of possibly leaving academia in favour of stability. Van Goethem is also not sure what the future holds. Being a postdoc can feel really thankless, he says. If you work extra hours, that’s just seen as par for the course, he says. “If you publish a paper, that is your job. If you train someone in your free time, that’s just being a good postdoc. It is extremely hard to stand out.” Postdoc positions are not for the faint of heart, he concludes. “When you see your contemporaries doing regular jobs that didn’t require much studying, and they’re earning more and seeming happier, you can imagine that the enthusiasm for this career path dwindles very fast.”