Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Electrons in stacked sheets of staggered graphene collectively act as though they have fractional charges at ultralow temperatures.Credit: Ramon Andrade 3DCiencia/Science Photo Library

Two teams have observed that electrons, which usually have a charge of −1, can behave as if they had fractional charges (such as −2/3) — and do so without being nudged by an external magnetic field. It’s the first time this ‘fractional quantum anomalous Hall effect’ has been observed experimentally, and physicists are scratching their heads over exactly how it works. It’s a fundamental discovery that might also someday have practical applications: fractionally charged particles are a key requirement for a certain type of quantum computer. “I don’t know anyone who’s not excited about this,” says condensed-matter physicist Pablo Jarillo-Herrero.

Nature | 7 min read

Reference: Nature paper 1 & paper 2

Japanese tits (Parus minor) flutter their wings to invite their mate to enter the nest first. Scientists who observed eight breeding pairs of wild tits noticed that when one of the birds sat in front of the next box and fluttered its wings, the other would go in first. It’s the first documented evidence of birds using a symbolic gesture: one that has a specific meaning (like waving ‘goodbye’) but isn’t simply pointing at an object of interest. “It implies that birds have a level of understanding of symbolism that probably a lot of people wouldn’t have given them credit for before,” says ornithologist Mike Webster.

Scientific American | 4 min read

Reference: Current Biology paper

Offering researchers more money or time doesn’t seem to push them towards higher-risk, higher-reward projects. A survey asked more than 4,000 US-based academics how various hypothetical grants would influence their research strategy. Only tenured professors were willing to pursue riskier research with longer-running grants. And respondents were very unwilling to take less money in exchange for a longer grant. The results seem to suggest that “fairly reasonable changes in the structure of one particular individual grant don’t do enough to change the overall incentive structure”, says Carl Bergstrom, a biologist who has studied science-funding models.

Nature | 6 min read

Reference: arXiv preprint (not peer reviewed)

Infographic of the week

Table of Contents

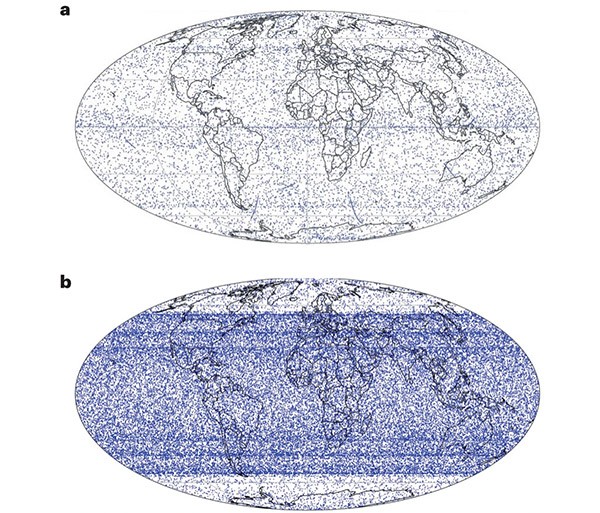

A. Williams et al./Nature Sustainability

The number of satellites and other space debris in low-Earth orbit (a) is on track to exceed 100,000 in the next ten years as SpaceX, OneWeb, GuoWang and Amazon plan to launch around 65,000 satellites (b). Policymakers must come up with a plan for space sustainability, argues a group of astronomers. (Nature Sustainability | 10 min read) (A. Williams et al./Nature Sustainability)

Features & opinion

More than two billion people worldwide lack access to reliable and safe drinking water. Changing that means tackling complex challenges that can only be solved by working alongside local communities, say four researchers with first-hand knowledge of water scarcity. “People are not voiceless, they simply remain unheard,” says water-governance scholar Farhana Sultana. “The way forward is through listening.”

Nature | 8 min read

You might have heard this one before: astronomer Fred Hoyle coined the phrase ‘Big Bang’ to make fun of a theory of the Universe’s origins that he disliked. Wrong, writes historian Helge Kragh. Hoyle did originate the catchy term — in a 1949 popular-science talk for BBC radio — but it was never intended as ridicule. And most people, including Hoyle, pretty much ignored it for decades afterwards. In 1965, the discovery of the cosmic microwave background signalled the triumph of the theory, ‘Big Bang’ made it into a New York Times headline, and the term snowballed into the popular lexicon.

Nature | 9 min read

Climate forecasting powered by artificial-intelligence (AI) algorithms could replace the equation-based systems that guide global policy. Some scientists are developing AI emulators that produce the same results as conventional models but do so much faster, using less energy. Others are hoping that AI systems can pick up on hidden patterns in climate data to make better predictions. Hybrids could embed machine-learning components inside physics-based models to gain better performance while being more trustworthy than models built entirely from AI. “I think the holy grail really is to use machine learning or AI tools to learn how to represent small-scale processes,” says climate scientist Tapio Schneider.

Nature | 8 min read

Tonight, I’ll be keeping an eye on Corona Borealis, a constellation that is home to a white dwarf star. Once every 80 years or so, the white dwarf blows off the material it has syphoned off from a nearby red giant star in a spectacular cosmic explosion visible to the naked eye — and it’s expected to take place sometime before September.

Help to keep this newsletter on a stable trajectory by sending your feedback to briefing@nature.com.

Thanks for reading,

Katrina Krämer, associate editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Flora Graham, Smriti Mallapaty and Sarah Tomlin

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma