The Forbidden Garden: The Botanists of Besieged Leningrad and Their Impossible Choice Simon Parkin Scribner (2024)

After Simon Parkin’s account of the siege of Leningrad and the fate of the world’s first proper seed bank, after his postscript, afterword and acknowledgements, there are nine pages that — for people who know the story — are worth the rest of the book combined.

Conservation policies must address an overlooked issue: how war affects the environment

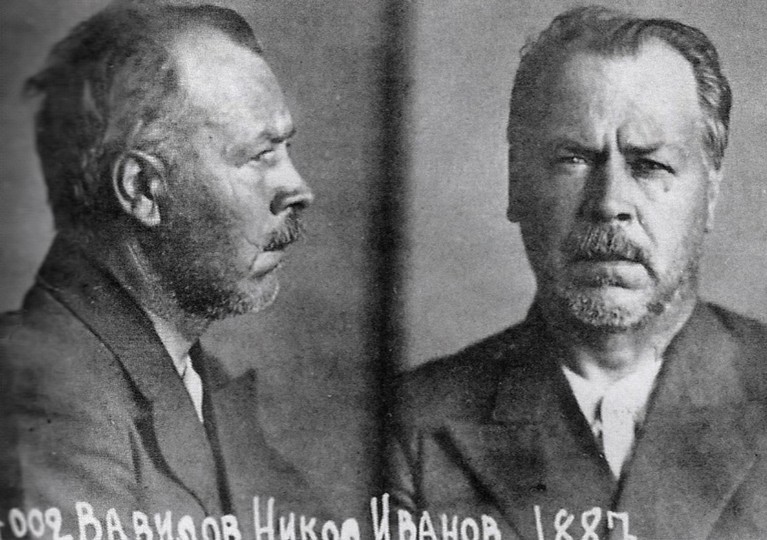

It’s the staff roll call, meticulously assembled from institutional records and other sources, of what Parkin calls simply the Plant Institute. More fully, it was then called the Bureau of Applied Botany and Plant Breeding, which, in 1992, became the Vsesoyuzny Institut Rastenievodstva in St Petersburg, Russia. The institute was founded in the nineteenth century by German horticulturalist and botanist Eduard August von Regel and was vastly expanded by Russian Soviet agronomist Nikolai Vavilov.

The list does not make for easy reading.

Starvation, starvation, starvation, died at front … Between 8 September 1941 and 27 January 1944, while German forces besieged the city, the institute’s staff members sacrificed themselves, one by one, to protect a collection for which the whole raison d’être was to one day save humanity from starvation.

German soldiers on the outskirts of besieged Leningrad in 1941.Credit: IanDagnall Computing/Alamy

While, just around the corner, Leningrad’s Hermitage art museum’s two million artefacts were squirrelled away for safety, the Plant Institute faced problems of a different magnitude. Its 2,500 species — comprising hundreds of thousands of seeds, rhizomes and tubers — were alive and needed to be kept at a degree or two above freezing. Many of them, some 380,000 examples of potato, rye and other crops, would survive only if planted annually. This in a city that was being shelled for up to 18 hours a day and where the temperature could — and, in February 1942, did — fall to around −40 °C.

The Burning Earth: how conquest and carnage have decimated landscapes worldwide

Johan Eichfeld, the institute’s director after Vavilov’s disappearance (his arrest and secret imprisonment, in fact), was evacuated to the town of Krasnoufimsk in the Ural Mountains. A train containing a large part of the collection was to follow, but never made it. Eichfeld eventually got word to the institute, begging his staff to eat the collection and save themselves. But they had lost the collection to hunger once before, during the dreadful winter of 1921–22. They weren’t going to do so again.

January and February 1942 were the worst months. In the dark, freezing building of the institute, workers prepared seeds for preservation. They divided the collection into duplicate parts, while bombs burst around them.

The Germans never did succeed in overrunning Leningrad. But rats did. That first winter, hordes of vermin swarmed the building. No effort to protect the collection proved rat-proof: they even managed to break into ventilated metal boxes to devour the seeds. Still, of the 250,000 items in the institute’s collection, only 40,000 were consumed by vermin or failed to germinate after the war.

The institute had many potato varieties.Credit: DeAgostini/Getty

The seed bank survived, after a fashion. Agronomist and Stalinist poster child Trofim Lysenko — Vavilov’s inveterate opponent — maintained that the whole enterprise was disordered and, until the mid-1960s, the collection was allowed to deteriorate.

Contributions from abroad helped to sustain the institute after the war. For instance, in 1958 and the years that followed, it received potatoes and other seeds from Tucumán university in Argentina, thanks to a chance meeting between the institute’s director, Pjotr Zhukovski, and a German plant collector, Heinz Brücher. But, in the 1990s it emerged that, during the war, Brücher had been an officer in the SS Nazi paramilitary group, leading a special commando unit charged with raiding Soviet agricultural experimental stations. So Brücher hadn’t really been donating valuable potato varieties after all: he had been returning them.

The fortunes of war

Table of Contents

The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad is a thoughtful and desperately sad account of human generosity and sacrifice. The institute played an important part in feeding the post-war world. Several high-yielding and disease-resistant strains of wheat and blight-resistant strains of potato originated there. If the book falls short anywhere, it’s at exactly the place Parkin himself identifies. In this city laid to waste, among the bodies of the fallen, the frozen — in some hideous cases, half-eaten — starving people make for rotten witnesses of their own condition. The author had only scraps to go on.

Nikolai Vavilov, whose initial death sentence was later reduced to 20 years’ imprisonment, died from starvation in the winter of 1943.Credit: The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD)