The Arctic is feverish and on fire—at least parts of it are. And that’s got scientists worried about what it means for the rest of the world.

The thermometer hit a likely record of 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees Fahrenheit) in the Russian Arctic town of Verkhoyansk on Saturday, a temperature that would be a fever for a person—but this is Siberia, known for being frozen. The catastrophic oil spill from a collapsed storage tank last month near the Arctic city of Norilsk was partly blamed on melting permafrost. In 2011, part of a residential building in Yakutsk, the biggest city in the Sakha Republic, collapsed due to thawing and subsidence of the ground.

Last August, more than 4 million hectares of forests in Siberia were on fire, according to Greenpeace. This year the fires have already started raging much earlier than the usual start in July, said Vladimir Chuprov, director of the project department at Greenpeace Russia.

Persistently warm weather, especially if coupled with wildfires, causes permafrost to thaw faster, which in turn exacerbates global warming by releasing large amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas that’s 28 times stronger than carbon dioxide, said Katey Walter Anthony, a University of Alaska Fairbanks expert on methane release from frozen Arctic soil.

“Methane escaping from permafrost thaw sites enters the atmosphere and circulates around the globe,” she said. “Methane that originates in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic. It has global ramifications.”

And what happens in the Arctic can even warp the weather in the United States and Europe.

In the summer, the unusual warming lessens the temperature and pressure difference between the Arctic and lower latitudes where more people live, said Judah Cohen, a winter weather expert at Atmospheric Environmental Research, a commercial firm outside Boston.

That seems to weaken and sometimes even stall the jet stream, meaning weather systems such as those bringing extreme heat or rain can stay parked over places for days on end, Cohen said.

According to meteorologists at the Russian weather agency Rosgidrome t, a combination of factors—such as a high pressure system with a clear sky and the sun being very high, extremely long daylight hours and short warm nights—have contributed to the Siberian temperature spike.

-

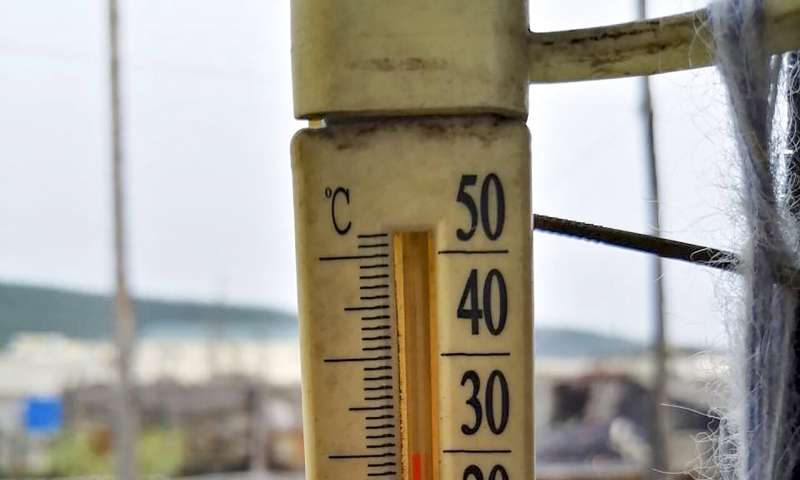

In this handout photo taken Sunday, June 21, 2020 and provided by Olga Burtseva, an outside thermometer shows 30 Celsius (86 F) around 11 p.m in Verkhoyansk, the Sakha Republic, about 4660 kilometers (2900 miles) northeast of Moscow, Russia. A record-breaking temperature of 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees Fahrenheit) was registered in the Arctic town of Verkhoyansk on Saturday, June 20 in a prolonged heatwave that has alarmed scientists around the world. (Olga Burtseva via AP)

-

In this handout photo taken Sunday, June 21, 2020 and provided by Olga Burtseva, children play in the Krugloe lake outside Verkhoyansk, the Sakha Republic, about 4660 kilometers (2900 miles) northeast of Moscow, Russia. A record-breaking temperature of 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees Fahrenheit) was registered in the Arctic town of Verkhoyansk on Saturday, June 20 in a prolonged heatwave that has alarmed scientists around the world. (Olga Burtseva via AP)

-

In this handout file photo dated Tuesday, June 2, 2020, provided by the Russian Marine Rescue Service, rescuers work to prevent the spread from an oil spill outside Norilsk, 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles) northeast of Moscow, Russia. Russian President Vladimir Putin on Friday June 19, 2020, has ordered his government to fully repair environmental damage from a massive fuel leak in the Arctic. A power plant in the Siberian city of Norilsk leaked 20,000 tons of diesel fuel into the ecologically fragile region when a storage tank collapsed on May 29. (Russian Marine Rescue Service via AP, File)

-

This handout photo provided by Vasiliy Ryabinin shows oil spill outside Norilsk, 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles) northeast of Moscow, Russia, Friday, May 29, 2020. Russian authorities have charged Vyacheslav Starostin, the director of an Arctic power plant that leaked 20,000 tons of diesel fuel into the ecologically fragile region on May 29, 2020, with violating environmental regulations. An investigation is ongoing Monday JUne 8, 2020, into the alleged crime, that could bring five years in prison if Starostin is found guilty. (Vasiliy Ryabinin via AP)

-

In this Thursday, June 18, 2020, handout photo provided by the Russian Emergency Situations Ministry, workers prepare an area for reservoirs for soil contaminated with fuel at an oil spill outside Norilsk, 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles) northeast of Moscow, Russia. Russian President Vladimir Putin has ordered his government to fully repair environmental damage from a massive fuel leak in the Arctic. A power plant in the Siberian city of Norilsk leaked 20,000 tons of diesel fuel into the ecologically fragile region when a storage tank collapsed on May 29. (Russian Emergency Situations Ministry via AP)

“The ground surface heats up intensively. .… The nights are very warm, the air doesn’t have time to cool and continues to heat up for several days,” said Marina Makarova, chief meteorologist at Rosgidromet.

Makarova added that the temperature in Verkhoyansk remained unusually high from Friday through Monday.

Scientists agree that the spike is indicative of a much bigger global warming trend.

“The key point is that the climate is changing and global temperatures are warming,” said Freja Vamborg, senior scientist at the Copernicus Climate Change Service in the U.K. “We will be breaking more and more records as we go.”

“What is clear is that the warming Arctic adds fuel to the warming of the whole planet,” said Waleed Abdalati, a former NASA chief scientist who is now at the University of Colorado.

© 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.

Citation:

The Arctic is on fire: Siberian heat wave alarms scientists (2020, June 24)

retrieved 24 June 2020

from https://phys.org/news/2020-06-arctic-siberian-alarms-scientists.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.