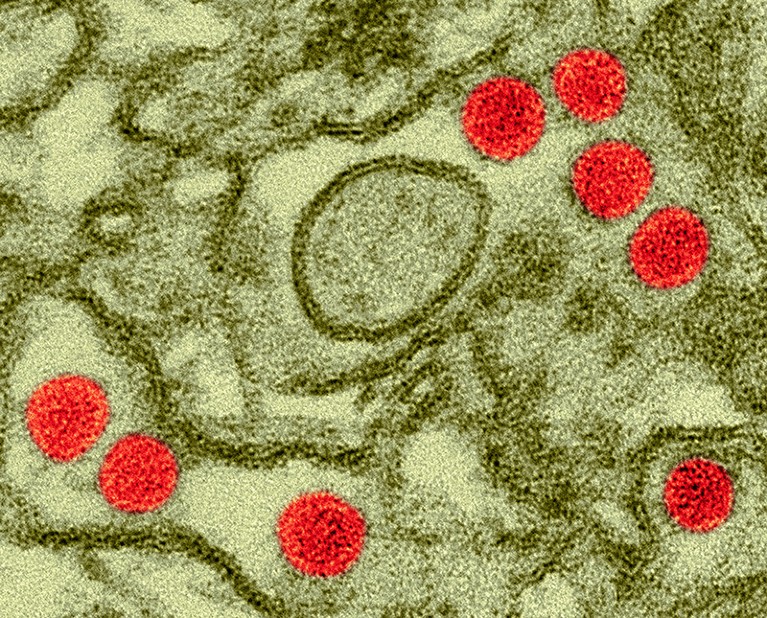

Scientists gave doses of Zika virus (red; artificially coloured) to healthy volunteers in the hope that a similar protocol could be used to trial vaccines.Credit: Dennis Kunkel Microscopy/Science Photo Library

For the first time, scientists have deliberately infected people with Zika virus to learn whether such a strategy could help to test vaccines against the pathogen.

The virus can cause severe birth abnormalities in babies born to parents infected during pregnancy. It also has been associated with neurological problems in adults, although those cases are rare. But infected study participants had only mild symptoms, and none became pregnant during or immediately after the trial. The results raise hopes that ‘human challenge’ programmes — in which volunteers are exposed to a pathogen in a controlled setting — could make it feasible to test vaccines at a time when Zika incidence is low.

“This is a great scientific gain in terms of the development of a vaccine,” said Rafael Franca, an immunologist at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Ribeirão Preto, Brazil. The results are scheduled to be presented today at the annual meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in Chicago, Illinois.

Zika’s rise and fall

Table of Contents

A surge of neurological congenital problems associated with Zika, which is spread by mosquitoes, led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a public-health emergency of international concern in February 2016. Dozens of vaccine candidates were proposed. Since the initial outbreaks, however, the number of infections has plummeted, halting the progress of clinical trials.

Hundreds of people volunteer to be infected with coronavirus

That’s why scientists began to discuss human challenge studies. “Our concern was that the epidemic was waning and that traditional [large] clinical trials for efficacy would not be able to be done because there wouldn’t be enough cases of Zika,” says Anna Durbin, an infectious-disease specialist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland, and a co-author of the study.

In 2022, after a long process to address ethical concerns around the study, Durbin and her team recruited 28 healthy women, aged 18 to 40, who were neither pregnant nor lactating. All agreed to be admitted to a research facility and remain there until they were no longer infectious; they stayed at the unit for 9 to 16 days. They were tested for pregnancy several times before receiving the virus, to avoid the risk of congenital problems associated with Zika, and were counselled to use birth control for at least two months after the study.

Hope for smaller trials

The researchers injected 20 participants with one of two strains of Zika virus and eight with placebo. All of the participants who received the virus were infected; of those, 95% developed a rash — a common symptom of Zika — and 65% had joint pain. None of the placebo recipients had those symptoms.

Durbin says the findings indicate that the two strains of Zika administered in the trial can be safely and effectively used to infect participants in a Zika vaccine trial. She estimates that the controlled human infection model could be used in a phase III clinical trial for vaccine efficacy with as few as 50 to 100 participants. “With the challenge model, where you have 100% of infections, you could get an efficacy result with many fewer people” than in a conventional trial, says Durbin.

But Franca expressed concern that larger challenge studies could raise the risk of rare neurological side effects, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome, which causes muscular weakness and sometimes paralysis. And Durbin says that even after a challenge study, it would still be necessary to do a clinical trial involving a few thousand participants, to establish a vaccine’s safety.

Change of heart

The new study represents a turnaround in the thinking about challenge trials. In early 2017, a report by researchers convened by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research concluded that the risks of a human-infection study for Zika, at that time, surpassed the potential benefits.

How a simple ‘thank you’ could improve clinical trials

One of the researchers involved, Ricardo Palacios, a specialist in vaccine development currently based in Siena, Italy, says that he and other authors of the report were concerned about sexual transmission of Zika virus from study participants to people outside the study. And they were uncertain whether regulatory authorities would consider this type of study for a vaccine approval.

But “from that time to now, we learnt a lot,” says Palacios. “Now we know that the risk of the virus being transmitted to another person through sexual relationships is limited and something that can be controlled,” he says. And regulators have signalled that they might consider data from human challenge trials in vaccine development, “in particular for those diseases that don’t have enough incidence to test in the field.”

Despite the low number of Zika cases, researchers say that it’s important to continue the efforts to develop a vaccine, because the virus might make a comeback. “Infections are much lower than they were during the epidemic in 2016. However, they are still occurring,” says Neil French, an infectious-disease specialist at the University of Liverpool, UK, who is involved in a Zika vaccine-development project. “The justification for a vaccine remains strong.”