Microorganisms have shaped Earth for almost four billion years. At least a trillion microbial species sustain the biosphere — for instance, by producing oxygen or sequestering carbon1. Microbes thrive in extreme environments and use diverse energy sources, from methane to metals. And they can catalyse complex reactions under ambient temperatures and pressures with remarkable efficiency.

The potential to exploit these microbial abilities to substantially reduce the impact of human activities on the planet has been recognized by many2. And bacteria or fungi are already being used to produce materials, fuels and fertilizers in ways that reduce energy consumption and the use of fossil-fuel feedstocks, as well as to clean up waste water and contaminants3.

Despite their wide-ranging potential, however, microbe-based technologies remain largely overlooked in international plans to combat climate change or reduce the loss of biodiversity4. For example, discussions about the role of microbial technologies in achieving fossil-free alternatives to current products and processes were minimal or absent at the United Nations conferences of the parties (COPs) in 2023 and 2024 on climate change, and on biodiversity in 2022 and 2024 (see Nature 636, 17–18; 2024).

Is the COP29 climate deal a historic breakthrough or letdown? Researchers react

To better leverage microbiology in addressing climate change and other sustainability challenges, the International Union of Microbiological Societies and the American Society for Microbiology brought us (the authors) together in December 2023 — as a group of microbiologists, public-health scientists and economists with expertise in health, energy, greenhouse gases, agriculture, soil and water. In a series of meetings, we have assessed whether certain microbe-based technologies that are already on the market could contribute to sustainable solutions that are scalable, ethical and economically viable. We have identified cases in which the technical feasibility of an approach has already been demonstrated and in which solutions could become competitive with today’s fossil-based approaches in 5–15 years.

This work has convinced us that microbe-based interventions offer considerable promise as technological solutions for addressing climate change and — by reducing pollution and global warming — biodiversity loss. Here, we explain why they could be so important5 and highlight some of the issues that we think microbiologists, climate scientists, ecologists and public-health scientists, along with corporations, economists and policymakers, will need to consider to deploy such solutions at scale6.

Microbial possibilities

Table of Contents

The use of genomics, bioengineering tools and advances in artificial intelligence are greatly enhancing researchers’ abilities to design proteins, microbes or microbial communities. Using these and other approaches, microbiologists could help to tackle three key problems.

First, many products manufactured from fossil fuels (energy, other fuels and chemicals) could be produced by ‘feeding’ microbes with waste plastics, carbon dioxide, methane or organic matter such as sugar cane or wood chips.

Microbes that grow underneath artificial floating islands can transform lakes from net methane sources into carbon sinks.Credit: WaterClean Technologies

Among the many companies applying microbe-based solutions to address climate change, LanzaTech, a carbon-upcycling company in Skokie, Illinois, is working on producing aviation fuel on a commercial scale from the ethanol produced when microbes metabolize industrial waste gases or sugar cane. Meanwhile, the firm NatureWorks in Plymouth, Minnesota, is producing polymers, fibres and bioplastics using the microbial fermentation of feedstocks, such as cassava, sugar cane and beets.

Second, microbes could be used to clean up pollution — from greenhouse gases, crude oil, plastics and pesticides to pharmaceuticals.

For instance, a start-up firm called Carbios, based in Clermont-Ferrand, France, has developed a modified bacterial enzyme that breaks down and recycles polyethylene terephthalate (PET), one of the most common single-use plastics. Another company — Oil Spill Eater International in Dallas, Texas — uses microbes to clean up oil spills, and large waste-management corporations in North America are using bacteria called methanotrophs to convert the methane produced from landfill (a more potent greenhouse gas than CO2) into ethanol, biofuels, polymers, biodegradable plastics and industrial chemicals.

Drill, baby drill? Trump policies will hurt climate ― but US green transition is underway

The company Floating Island International in Shepherd, Montana, is even building artificial floating islands on lakes and reservoirs that have been polluted by excessive nutrient run-off, so that methane-metabolizing microbes (which colonize the underside of the islands) can remove methane originating from lake sediments. The goal in this case is to transform inland lakes and reservoirs from net methane sources into carbon sinks.

Finally, microbes could be used to make food production less reliant on chemical fertilizers and so more sustainable.

The chemical process needed to produce ammonia for fertilizer involves burning fossil fuels to obtain the high temperatures and pressures needed (up to 500 °C and 200 atmospheric pressures), releasing 450 megatonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere each year (1.5% of all CO2 emissions)7. Furthermore, excess chemical fertilizers that flow into rivers, lakes and oceans cause algal blooms, which enhance the emission of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas that is more potent than either CO2 or methane.

Many bacteria and archaea can be used to produce nitrogen fertilizer with much lower greenhouse-gas emissions than synthetic fertilizers. This is because the microbes fix nitrogen at room temperature and at sea-level atmospheric pressure using enzymes known as nitrogenases that convert atmospheric nitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3).

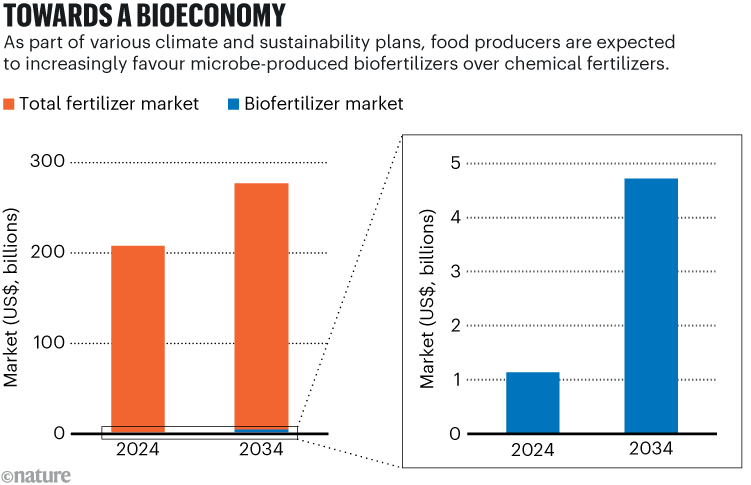

Several companies are now selling biofertilizers, which are formulations containing bacteria called rhizobia or other microbes that can increase the availability of nutrients to plants (see ‘Towards a bioeconomy’ and go.nature.com/3fs2xqf). A growing number of microbial biopesticides are also offering food producers a way to control crop pests without harming human or animal health or releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere8.

Source: https://www.precedenceresearch.com/fertilizer-market

Keeping it safe

As more microbe-based solutions enter the market — whether bioengineered or naturally existing — biosafety considerations will become increasingly important.

Many solutions, such as using bacteria to degrade crude oil or plastics, have been shown to be effective and safe in a laboratory setting9. Yet scaling up their use to the levels needed to reduce global emissions or global biodiversity loss could lead to unforeseen complications.

Bacteria are being designed to break down plastic waste.Credit: Carbios–AgenceSkotchProd

Certain safeguards — designing bacteria that can persist in an ecosystem for only a short time or that can exist under only specific environmental conditions — are already being developed and applied4. And, in a similar way to phased clinical trials in biomedical research, laboratory experiments could be followed by contained tests in the outdoor environment, which could then be followed by larger-scale field testing. Investigators will also need to monitor systems over time, which could involve the sequencing of environmental DNA from waste water and other approaches that are used in infectious-disease surveillance.

Ultimately, the effective deployment, containment and monitoring of large-scale microbe-based solutions will require scientific communities, governments and corporations to collaboratively develop evidence-based policies and engage in clear and transparent communication about the enormous opportunities and the potential risks.