From CRISPR gene editing to protein-structure predictions driven by artificial intelligence, great innovations stem from interdisciplinary research. Solutions to climate change, biodiversity loss, health inequities and other global crises will also rely on insights that bridge many fields.

Yet interdisciplinary research is still sidelined in many countries. Even though these papers attract more citations1 and have more impact on research2, interdisciplinary research proposals tend to be less likely to receive funding than are those with a narrower scope3.

Some countries have adjusted their research funding strategies accordingly. For example, between 2016 and 2018, UK research councils awarded 30% more grants to interdisciplinary investigators than they had a decade earlier, with 44% of funded projects in 2018 spanning at least two research subjects4. A similar move has been made in the United States: between 2015 and 2020, university departments that submitted some interdisciplinary grant proposals received almost five times more funding — in terms of total and individual awards — from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF) than did those that submitted in only one discipline5.

‘Male-dominated campuses belong to the past’: the University of Tokyo tackles the gender gap

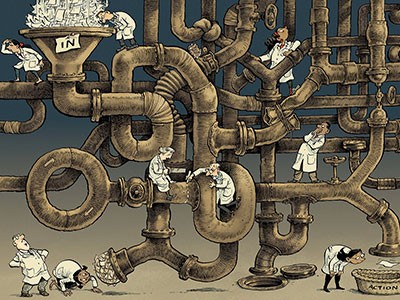

Alas, this isn’t the case in Japan. The nation’s funding agencies still mostly support research in tight disciplinary boundaries, such as engineering or chemistry. Specialists who evaluate these grant proposals tend to favour work in fields that they are familiar with over interdisciplinary studies they do not understand well.

This narrow approach is leading to substantial underfunding of interdisciplinary research in Japan. It also means that the nation is missing out on breakthroughs. Japan’s natural resources are limited, and its economy has long relied on science and technology. The decline in its research and innovation is unmistakable, as indicated by the country’s share of the world’s top 10% of most-cited research articles, which has dropped from 6% to 2% over the past two decades or so.

As scientists and engineers based in Japanese research institutions, we urge the government and funding agencies to do more to support interdisciplinary research — or risk eroding the country’s global standing in science and its economy. Here we highlight five directions to foster such a shift.

Fund people, not projects

Table of Contents

We argue that Japanese funding agencies should pivot from funding projects to supporting talented researchers. Such a model has proven to be effective in leading institutions worldwide. For example, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s (HHMI) Investigator Program provides outstanding scientists with flexible, long-term funding to pursue high-impact biomedical research — some US$11 million over a seven-year term, which can be renewed. This approach has led to groundbreaking discoveries, including the mechanistic understanding of circadian rhythms, the computational prediction of protein folding and the discovery of RNA interference.

Japanese research is no longer world class — here’s why

Similarly, in Germany, the Max Planck Society prioritizes curiosity-driven research that has long-term objectives over immediate applications. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and providing institute directors with generous internal funding, free from the continual need to secure external grants, this strategy has enabled breakthroughs including the development of CRISPR–Cas9 as a gene-editing tool and structural insights into ribosomes.

Japan does have some programmes to support talented researchers, but these are too timid. The Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), for example, dedicate some funds to basic science and some to curiosity-driven research. But the JST adopts a top-down approach, which often favours research on trending topics and can miss more-original ideas or projects . And the annual budget for the JSPS’s main grant programme, the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI), has remained stagnant for the past decade. Adjusted for inflation and the weakening yen, the average funding per project has halved since 2013.

However, one Japanese institution has adopted researcher-focused funding with great success: the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST). Unlike national universities, which are funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, OIST is a private university that is funded by Japan’s Cabinet Office. Launched in 2011, it has a horizontal organizational structure and a strong commitment to diversity and interdisciplinary collaboration (see ‘Steps to success’). OIST is now ranked as Japan’s leading research institute by the Nature Index, and around 20% of its publications involve contributions across more than one discipline. More Japanese institutions should follow its lead.

Embrace high-stakes projects

Interdisciplinary research is often perceived as riskier than more conventional, single-discipline work. This might be because it can be hard to learn concepts and methods, and even communicate efficiently, across disciplines. And priorities between fields can conflict.

To overcome these challenges, Japanese funding agencies should consider adopting a ‘high risk, high impact’ funding model, similar to that of the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which anticipates a success rate of just 50%. They should recognize that even ‘unsuccessful’ high-risk projects can generate valuable knowledge, contributing to broader scientific and technological advancements. The DARPA funding model has inspired others, such as the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), launched in the NIH to drive biomedical breakthroughs6.

How to improve assessments of publication integrity

Another example is the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub in California, which supports interdisciplinary teams comprising biologists, engineers and data scientists to work on ambitious goals, such as the eradication of infectious diseases. It provides substantial funding over several years to enable teams to pivot research directions in response to emerging challenges. Success is assessed through regular milestone-based evaluations. Projects that show limited potential are promptly terminated, ensuring that resources can be reallocated to more-promising endeavours.

In Japan, we are not advocating for existing funds to be redistributed. Rather, Japanese policymakers should allocate money to high-risk, high-reward projects from a separate pot, managed through dedicated DARPA-like programmes.

Expand grant panels

Initiatives such as the JST’s Diversity and Inclusiveness programme aim to lessen the homogeneity of the research workforce — for example, through awards and networking opportunities for women in science and by providing support or extensions for life events as well as for childcare and caregiving commitments — which tend to fall mostly on women (see page 295). This is laudable, but these efforts should be more widespread: they should be extended across genders and also include funding agency officers, programme managers and reviewers.

The crewed research submersible Shinkai 6500 has conducted more than 1,700 dives.Credit: Associated Press/Alamy

Japan’s funding agencies should also ensure that their own decision makers are less homogeneous in terms of their discipline, background, gender, age, nationality and culture. This would help to favour interdisciplinary research, which by nature weaves different approaches together and can benefit from being planned, conducted and assessed by a diverse community.

The role of immigration in boosting diversity should also be recognized.