Her sister’s life-threatening experience with diabetes was a wake-up call for Mikayla Olsten.

In 2016, when Olsten was 14 years old, her youngest sibling Mia landed in intensive care with failing kidneys and fluid in her lungs. It was ketoacidosis, a complication of type 1 diabetes (T1D) that is often the first sign that the body is not making enough of the sugar-regulating hormone insulin. Blood glucose levels spike, as do toxic waste products, throwing organ function into disarray.

Although she is healthy today, Mia is one of the estimated 9 million people worldwide who must deal with the daily grind of T1D, carefully managing their blood sugar and insulin levels.

And the scare prompted the Olsten family to test Mikayla for signs of diabetes that often precede disease symptoms. There was no previous history of T1D in the family, but siblings of those affected are at a greatly elevated risk.

The results came back positive for four of the five T1D markers that physicians look for, each a type of ‘autoantibody’ that tells the immune system to attack insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Mikayla also had abnormal sugar metabolism — the disease process was already under way. Her odds of making it through secondary school without progressing to a diabetes diagnosis were about one in three, clinicians estimated.

Yet Mikayla, now 21 and studying exercise physiology at Brigham Young University–Idaho in Rexburg, continues to live diabetes-free — probably thanks to a drug called teplizumab.

Teplizumab is a type of antibody therapy. It blocks T cells, the ’attack dogs’ of the immune system, stopping them destroying insulin-producing islet cells in the pancreas. Mikayla received a two-week course of treatment in July 2016, as part of a clinical trial to test whether the therapy could help to keep T1D at bay.

The 76-person study1,2 — which ran from 2011 to 2018 — found that people who received the treatment developed diabetes symptoms after about five years, on average. That’s three years longer than the average delay for those who received the placebo.

Mikayla has remained diabetes-free for 6.5 years so far; others in the study have gone a decade or longer without needing to begin insulin therapy, which is currently the only effective way to manage the disease. Last November, drug authorities in the United States approved teplizumab for people 8 years and older who meet certain risk criteria.

The race to supercharge cancer-fighting T cells

“This is a huge, huge step forward for the field,” says Aaron Kowalski, president and chief executive of JDRF, a non-profit research organization in New York City that focuses on T1D. “It’s the first disease-modifying therapy in type 1 diabetes — ever.”

It’s also the first drug proven to delay the onset of an autoimmune disorder. And its development provides a roadmap for the discovery of pharmaceuticals to stall or prevent other conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

But identifying people who might benefit from such therapies remains a challenge: optimal screening strategies have yet to be established, and presymptomatic signs of disease are not well defined for each condition. Furthermore, because teplizumab offers only a temporary reprieve from T1D, researchers will need to find better approaches.

So, even as the field is “celebrating that we have teplizumab approved, it doesn’t mean we’re done”, says Jay Skyler, an endocrinologist at the University of Miami in Florida. “It means we’re just beginning.”

From treatment to prevention

Table of Contents

Teplizumab traces its roots to a New Jersey drug company called Ortho Pharmaceutical. There, scientists generated an early version of the antibody, dubbed OKT3. Originally sourced from mice, the molecule was able to bind to the surface of T cells and limit their cell-killing potential3. In 1986, it was approved to help prevent organ rejection after kidney transplants, making it the first therapeutic antibody allowed for human use.

But OKT3 was problematic: at high doses, it triggered a life-threatening complication known as cytokine release syndrome. And because it originated in mice, the human immune system would react against it, diminishing the drug’s potency over time. Researchers outside the company tweaked the formula to avoid these issues, and teplizumab was born.

The therapy initially entered clinical trials in 1999 as a treatment for people who had been newly diagnosed with T1D. A small study4, led by Kevan Herold, an immunologist now at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, found that a single course of the therapy could help people to maintain or even boost their insulin activity for years.

But a larger, follow-up trial ended in failure. Teplizumab proved no better than a placebo at reducing insulin usage and managing blood-sugar levels5. A similar drug called otelixizumab performed just as poorly6. Both therapies were abandoned.

It was a let-down for the diabetes field. But Herold wasn’t ready to give up.

Further analyses by Herold and his colleagues showed that the drug wore down the islet-targeted T cells7, and sent them into a state of partial exhaustion that helped to safeguard the pancreas against further assault. What’s more, many people seemed to benefit from the therapy, especially those who were younger or with less-advanced disease.

If the drug works best in those patients, reasoned Herold, then it might really shine if given before symptoms appear. So, in 2011 Herold spearheaded the launch of the Teplizumab Prevention Study, the one through which Mikayla and other at-risk individuals received their treatment.

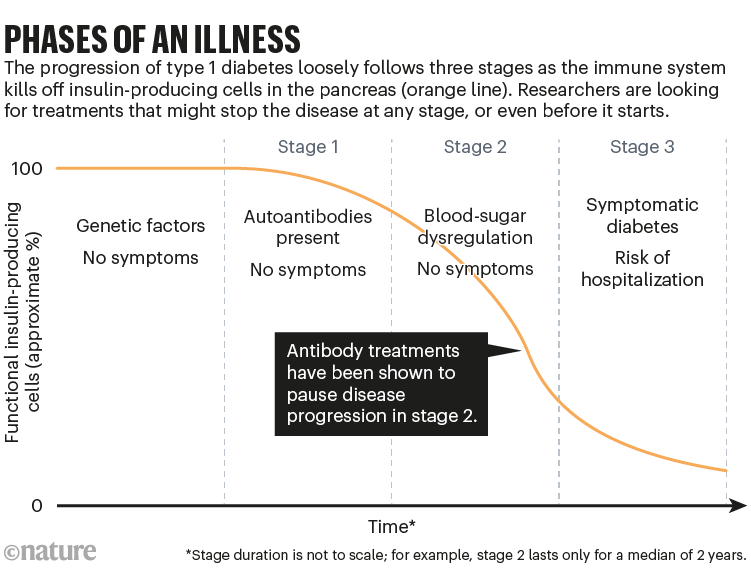

Those trial results underpinned the US Food and Drug Administration’s decision last year to approve teplizumab for people with stage 2 disease — those who do not yet have a T1D diagnosis, but who have two or more autoantibodies against islet cells and signs of altered sugar metabolism (see ‘Phases of an illness’).

Source: R. A. Insel et al. Diab. Care 38, 1964–1974 (2015)

A temporary reprieve

Since taking teplizumab in the clinical trial, Claire Wirt, a 16-year-old from Rochester, New York, has lived T1D-free for 7 years and counting. “It gets you so many childhood experiences without having to deal with diabetes 24/7,” she says. And biologically, that delay could reduce the stress that high blood-sugar levels can put on blood vessels, nerves and other organ systems, which add up over time.

But the reprieve isn’t cheap. The one-time treatment costs around US$194,000 — and that doesn’t include the expense of giving infusions or screening to find people who might benefit from the therapy.

Some researchers have questioned the therapy’s cost-effectiveness. But Ashleigh Palmer, co-founder and chief executive of drug firm Provention Bio in Red Bank, New Jersey, which acquired the rights to teplizumab in 2018, defends the pricing decision. “What we’re doing with our therapeutic here is game-changing,” Palmer says. “And I don’t see any reason why we shouldn’t price the product appropriately.”

Will pigs solve the organ crisis? The future of animal-to-human transplants

Analysts predict that global annual sales of teplizumab could exceed $250 million as a preventive therapy — plus a possible $1.5 billion or so if the drug is approved for people who have stage 3 disease. To that end, the company is running a 300-person trial to test the drug’s efficacy in children and teenagers who have been newly diagnosed with T1D.

In the pharmaceutical industry, all eyes are now on those sales in the United States. If Provention Bio and its marketing partner, the French drug giant Sanofi, can profit, then many more companies could begin exploring prophylactic therapies. But developing trials for autoimmunity remains risky, time-consuming and costly, says Jessica Dunne, a T1D scientist who previously led screening and prevention research at JDRF and Janssen in Raritan, New Jersey.

“So, what happens with teplizumab will be a little bit of a bellwether,” she says.

Janssen, which launched an ambitious ‘disease interception’ unit in 2015, shut its entire T1D division late last year, citing a “change in scientific strategy”, according to Janssen spokesperson Brian Kenney. But other big-name drug makers are planning to test their experimental diabetes agents as preventive medicines — and they credit teplizumab with setting the standard for regulatory and clinical success.

“It has shown drug developers that it is possible to modify the disease for a length of time that is meaningful to people,” says Johnna Wesley, head of T1D and chronic kidney disease research at Novo Nordisk, which is headquartered in Bagsværd, Denmark.

A long road

The company’s lead product for preventing T1D is a DNA-encoded therapeutic designed to stop the immune system attacking pancreatic cells8. Compared with teplizumab, which targets all T cells regardless of their function, Novo Nordisk’s drug is more narrowly tailored to T cells that attack the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas — which, according to Wesley, could offer safety and efficacy benefits.

Once the company has determined a reasonable dose level for people with established T1D, further development could include a prevention trial for people with stage 2 disease, Wesley says.

Academic groups are also evaluating several other drugs in that setting. Among them are other T-cell-targeted therapies — such as anti-thymocyte globulin, which is currently used to prevent organ rejection — as well as drugs that promote and preserve pancreatic capabilities directly.

Mikayla Olsten was screened for diabetes-related autoantibodies after her younger sister was hospitalized with complications from type 1 diabetes.Credit: Natalie Behring for Nature

But intervening at stage 2 might be too late, and do little more than delay the inevitable. As Richard Insel, former chief scientific officer at JDRF, points out: “The earlier you can get in there, the more likely you’ll be able to stop the disease in its tracks.” Some trials are testing drugs in people who have stage 1 disease — when diabetes-related autoantibodies are present but blood-sugar metabolism remains normal.

Other trials are looking even earlier than stage 1, searching for treatments that can be given in infancy to children who are at risk of T1D. Researchers have been exploring dietary changes for infants; introducing probiotic bacteria; and vaccinating against viruses, such as coxsackievirus B, that seem to trigger T1D symptoms. But giving children powdered insulin, which helps to train the immune system not to attack its own insulin-producing cells, has shown the greatest promise so far.

In early testing, children who received oral insulin alongside their breakfast developed a special type of immune cell, known as a regulatory T cell, that provides a layer of protection against future autoimmune attack9. A larger confirmatory trial is ongoing.

Auto focus

The T1D community is not alone in its quest to prevent autoimmunity. Those seeking to treat autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and multiple sclerosis (MS) have long followed the T1D prevention playbook in their own pursuit of disease-stalling agents.

“Type 1 diabetes has been our model,” says Paul Emery, a rheumatologist at the University of Leeds, UK.

The heart of the strategy for RA and MS is developing clearer definitions of what it means to be in a pre-disease state, and determining the various stages and diagnostics that could allow for rigorous prevention studies.

The ‘breakthrough’ obesity drugs that have stunned researchers

Rheumatologists have had some success with preventing disease using a T-cell-blocking agent called abatacept, with a preliminary study10 showing that the drug reduces joint inflammation and delays the development of RA in at-risk individuals. And for MS, clinicians have identified a drug that, in preliminary testing, wards off neurological symptoms in people who have early signs of nerve damage in the brain11.

Late last year, a team led by Darin Okuda, a neurologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, reported results for an anti-inflammatory drug called dimethyl fumarate. When given to people with a distinct type of anomalous brain scan, the drug helped to reduce the risk of MS by more than 80% compared with a placebo11. Over the course of 22 months, 3 of 44 people who received the drug progressed to MS, compared with 14 of 43 placebo-treated individuals.

“The results were the best that I could have wished for,” Okuda says.

One of the challenges of developing such drugs is the complexity of the clinical trials. First, researchers have to find appropriate trial participants, either by testing for early indicators of disease or for genetic risk factors. Then, they have to wait for years after the treatment to see who progresses.

“These studies take so dang long,” says Michael Haller, a paediatric endocrinologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

But the success with T1D could help. “Because of teplizumab,” Haller says, “I think a lot more people will get screened, and we’ll have a lot more folks interested.”

Screening for diabetes-related autoantibodies and other risk factors is unusual in most health-care systems, so many of the outreach and screening efforts are centred on families affected by T1D. That’s why Mikayla and Wirt had their blood tested — and it is this group of people that Provention Bio and Sanofi will target in their initial marketing of teplizumab.

But only around 15% of all people diagnosed with T1D have a previous family history of the disease, so researchers are studying ways of expanding the reach of screening.

Ahead of the problem

Some favour testing everyone for diabetes-related autoantibodies. This could be done at two time points in early childhood — say, at ages 2 and 6 — when the immune markers are most likely to appear. Clinicians in Israel have begun implementing this approach, blanket-testing thousands of toddlers.

Diabetes risk rises after COVID, massive study finds

Teplizumab is not yet available in Israel, so the efforts are focused on protecting against severe complications, explains Moshe Phillip, an endocrinologist at the Schneider Children’s Medical Center of Israel in Petach Tikvah, who is leading the effort. Studies show that children who are screened and tracked have around one-tenth the risk of ketoacidosis after T1D starts (see, for example, ref. 12). “That alone is a good reason to screen,” Phillip says.

Others think that DNA testing of blood spots collected at birth might be a better way to go. “With the genetics, you’re a step before the autoantibodies,” says Kristina Casteels, a paediatric endocrinologist at University Hospitals Leuven (UZ Leuven) in Belgium.

Across Europe, Casteels and her colleagues have genetically screened more than 100,000 newborns in this way, looking for gene variants that raise the chances of T1D. The parents of babies at greatest risk were then offered the chance for their child to participate in early-prevention trials — with probiotics or oral insulin. In other countries, newborns with high-risk genes are followed using regular autoantibody tests.

These approaches have strengths and weaknesses. Autoantibody tests aren’t standardized, so can vary in their accuracy, says Kimber Simmons, a paediatric endocrinologist at the University of Colorado’s Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes in Aurora. And with few resources available to counsel people, including physicians, about what it means to be at risk for T1D, such mass-screening efforts could lead to undue stress and clinical mismanagement, at least in the near term, says Carla Greenbaum, a diabetes investigator at the Benaroya Research Institute in Seattle, Washington.

Add in the costs of screening and of the drug therapies themselves, and it’s unclear whether health-care systems are prepared for wide-scale T1D prevention.

None of that is at the front of Mikayla’s mind, however. “At this point, I’m just grateful that I don’t have diabetes yet,” she says. “I know that I’m going to eventually have it, and I’m prepared for that. But right now, I’m more just loving my life.”