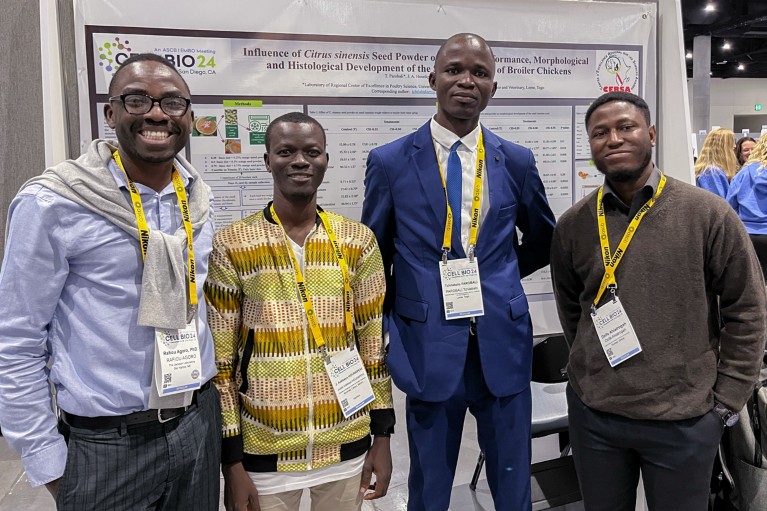

Pictured (left to right) Rafiou Agoro, Justin Hounkpevi, Tchilabalo Parobali, Dzifa AhiatrogahCredit: Rafiou Agoro

In April 2018, during my second year of a postdoctoral fellowship at New York University, I and my colleagues submitted an abstract to the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR), which was holding its annual meeting that September in Montreal, Canada.

As a citizen of Togo with limited experience of international conference travel, I saw the chance to attend this three-day meeting as an important career-development opportunity, enabling me to share scientific discoveries, learn from others and get updates on emerging technologies.

But unlike my colleagues from Europe, and despite us all having similar professional titles and immigration statuses in the United States, I needed a Canadian visa to attend. That’s because documentation requirements were more stringent for citizens of African countries than for applicants from elsewhere.

I identified a private company that provided visa services for the Canadian government, and six weeks before the conference I took a half-day’s leave to attend an appointment and paid Can$185 (then the equivalent of about US$140) to secure a passport stamp. A month later, I was given a second appointment, during which I received my passport and visa. The delay meant that registration, hotel reservations and airfares had increased in price.

How African scientists can give back to their home continent

Because most of the international meetings that welcome scientists from all over the world are held in the United States and Europe, scientists based outside these territories can find attendance particularly challenging, often requiring — as it did for me — months of paperwork to prepare.

This is especially the case for PhD students in Africa who have never travelled overseas before for work.

With this in mind, and informed by my own experiences, I partnered with Mohamed Cisse, a mathematician and computer scientist based in Guinea, to launch a travel-fellowship and mentoring programme. (Mohamed and I had already worked together to found the African Diaspora Scientists Federation (ADSF), a network of scientists who have developed their careers outside the continent.)

We approached the American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB) in 2023 with the aim of helping an interdisciplinary group of students to attend the following year’s Cell Bio meeting, an annual event held jointly with the European Molecular Biology Organization.

We wanted to create an ADSF–ASCB fellowship programme that would enable PhD students based in Africa to present their research in-person at the four-day Cell Bio meeting in San Diego, California, in December 2024.

Career resources for African scientists

We launched the call for fellowship applications in May and received more than 50 applications in a month, choosing four applicants for the pilot programme.

They were Tchilabalo Parobali, a biosecurity engineer at the University of Lomé in Togo; poultry scientist Justin Hounkpevi, also based there; Dzifa Ahiatrogah, a biomedical scientist at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana; and Gerard Quarcoo, an aquatic microbiologist at the Water Research Institute in Tamale, Ghana.

In June, we sent letters of invitation and all the paperwork for visa applications. It then took around four months before the applicants had their visa appointments at the US embassies in their countries.

Sadly, Gerard’s application was unsuccessful. But by mid-November, we were able to buy plane tickets for the other three. Because travel was the following month, the $1,200 round-trip ticket was twice as expensive as it would have been if purchased months in advance. The fellowship also covered hotel charges, the cost of airport–hotel transfers and ACSB membership for 2025.

Camaraderie

Table of Contents

To create a climate of pre-meeting camaraderie, the three fellows travelled together from Accra to the US west coast, a two-day journey with stopovers in Europe and the US east coast. I was in touch throughout their travels and met them before their poster sessions to offer advice, in between my own conference preparation and attendance at sessions.

I loved the practical aspects of their science, which I categorize as applied biology. Tchilabalo’s work, for example, uses a new dietary formula to increase poultry mass, which has societal benefits.

Listening to the three students reminded me of the importance of asking myself about the translational aspect of my own fundamental research, in which I use preclinical mouse models to pinpoint molecular mechanisms that improve the healthspan and lifespan of people with sickle-cell and kidney diseases.

I met the students each day for breakfast and lunch, using the time to review their plans for the day and provide advice if needed. We also took some evening walks together, and the fellows attended two receptions at which they networked with other scientists.