On 25 July, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) refused to approve the clinical use of lecanemab, a drug that can slow cognitive decline during the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The decision puts the EMA at odds with regulatory bodies across the world. For example, lecanemab has been approved in the United States, Japan, China, South Korea, Israel, the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom.

As a clinical neurochemist in Sweden who has spent 20 years researching Alzheimer’s disease, I think that the EMA has overestimated the risks of lecanemab and underestimated — or misunderstood — the benefits. The side effects are real, but the drug can buy a person invaluable months or years to spend with loved ones before dementia sets in. The reasons for the EMA’s decision should be interrogated.

Debate rages over Alzheimer’s drug lecanemab as UK limits approval

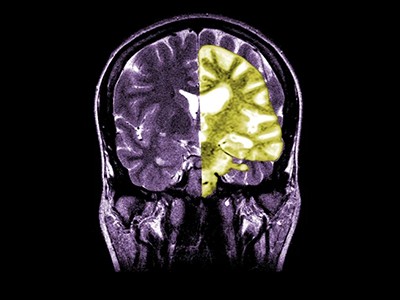

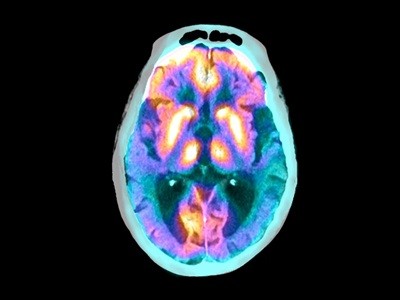

About 3.5% of those who take lecanemab experience adverse effects such as headaches or dizziness, caused by swelling or bleeding in the brain. These are serious risks — two deaths potentially due to brain bleeds have been reported in the United States — and must be considered. But US clinicians say that brain bleeds and swelling, which can be detected using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and other side effects are mostly manageable and less common than they had feared. Clinicians can also use genetic tests and MRI scans to reveal who is most at risk of serious complications, and they can give lecanemab to only those at low risk.

I worry that the EMA’s decision might reflect a broader emerging problem with the agency’s assessments of medicines. In April, the EMA invited me to take part in a scientific advisory meeting to discuss lecanemab, but I was excluded after disclosing that my research team and I work with companies that develop drugs or diagnostic tests for brain diseases, performing biomarker measurements to assess the extent of neurodegeneration in trial participants. This has included paid consultancy work for the Tokyo-based pharmaceutical firm Eisai, and Biogen, a biotechnology company headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts. These firms make lecanemab, and I advised them on the current state of biomarker research, to the best of my scientific knowledge.

My interactions with the EMA reflect a wariness of soliciting advice from scientists with links to pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies.

Blood tests could soon predict your risk of Alzheimer’s

On the surface, this precaution might seem sensible and straightforward, to prevent biased decision-making. But researchers with links to the pharmaceutical industry are often best placed to assess new medicines — and many universities see forging links with industry as a key part of a scientist’s job.

My work does not make me biased — I share my knowledge and have no other involvement with the companies. My laboratory does not profit when the firms use our methods. Whether a drug is approved is irrelevant to my work and income, so it has no effect on my ability to give objective advice. If this level of engagement with drug companies is to be grounds for exclusion from assessing a treatment, the EMA risks losing input from scientists with direct experience studying groundbreaking drugs. This systematic bias against knowledgeable and capable researchers and clinicians might slow drug approvals, because the advisers might be less familiar with the latest developments and make overly cautious decisions when told that the most important consideration is protecting people.

The EMA says there has been no recent policy change in regard to adviser selection, but that “interim measures” have been put in place in the wake of a ruling in March by the Court of Justice of the European Union. This ruling found that the EMA’s decision to reject a treatment for alcohol dependence in 2020 might have been biased by two specialists who had links to companies developing rival products.

Alzheimer’s drug with modest benefits wins backing of FDA advisers

Given the backdrop, you might argue that the EMA’s hands are tied.

But in my view, there are other ways to address this issue. The obvious solution is for the EMA’s conflict-of-interest policy to mimic that of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA’s policy states that a conflict of interest exists when an individual has financial or other interests that could be affected by their work on the committee. Assessing whether such interests exist would require some work by the EMA. But it prevents discrimination against researchers and clinicians at the forefront of their fields.

The FDA is not perfect — it has been criticized for its ties to the drug industry, and some scientists felt that lecanemab should not have been approved in the United States, given the risks. Some might feel that the EMA’s more-cautious approach is the right one. But, in my view, the clinical evidence that is accumulating suggests that the FDA made the correct call.

Eisai has appealed the EMA’s decision, giving the agency a second chance to approve lecanemab. If it does not, people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease across Europe will be left to deteriorate until they are beyond rescue. And if the EMA continues to tighten up its conflict-of-interest policy, it is rolling the dice on the future of many medicines for a host of diseases.

Competing Interests

Table of Contents

H.Z. has served on scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Abbvie, Acumen, Alector, Alzinova, ALZPath, Amylyx, Annexon, Apellis, Artery Therapeutics, AZTherapies, Cognito Therapeutics, CogRx, Denali, Eisai, LabCorp, Merry Life, Nervgen, Novo Nordisk, Optoceutics, Passage Bio, Pinteon Therapeutics, Prothena, Red Abbey Labs, reMYND, Roche, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers and Triplet Thera.