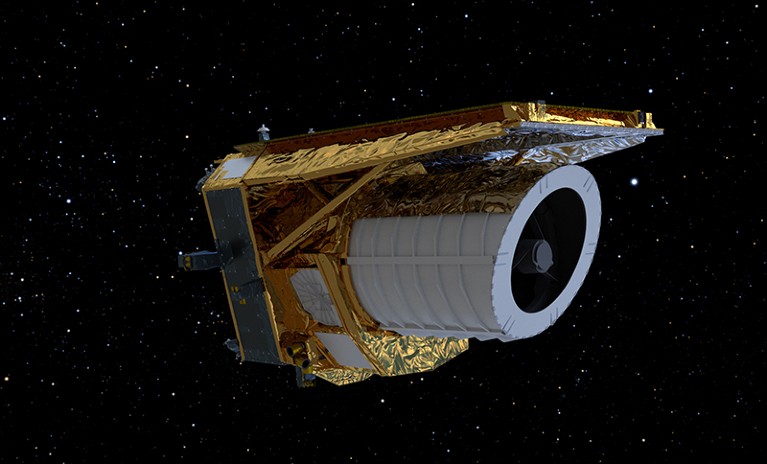

Engineers prepare the Euclid telescope for launch on a Falcon 9 rocket.Credit: SpaceX

Euclid, an ambitious Universe-mapping telescope, is about to open a new chapter in cosmology.

The €1.4-billion (US$1.5-billion) mission is the first in a new generation of experiments that were dreamed up in the aftermath of the discovery, 25 years ago, that the Universe’s expansion is accelerating. The goal is nowto understand what powers this acceleration — whether it’s caused by a ubiquitous property of space called dark energy, or by something else.

By mapping ordinary, visible matter — as revealed by the 3D positions of 1.5 billion galaxies — Euclid will also explore the distribution of dark matter. This enigmatic stuff is more than five times as abundant as ordinary matter, and forms a transparent scaffolding on the largest cosmic scales, which galaxies merely decorate like fairy lights on the branches of a tree.

Together, dark energy and dark matter constitute an estimated 95% of the Universe’s contents, but their nature and properties are still poorly understood. According to Yannick Mellier, an astronomer at the Paris Astrophysical Institute, the results could amount to “a revolution in our understanding of the physical laws of nature”. Mellier leads the Euclid Consortium, which includes 1,600 scientists from 17 countries.

Two cameras are better than one

Table of Contents

The 1,921-kilogram Euclid spacecraft, which carries a 1.2-metre-wide primary mirror made of very stiff silicon carbide, is scheduled to launch on 1 July from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket — unusually, for a European Space Agency (ESA) mission. (Depending on weather and other factors, the date could slide by a day or more.)

The telescope will watch the sky with two cameras simultaneously: one in the visible spectrum and the other in the infrared whileollowing Earth’s orbit around the Sun from a distance of 1.5 million kilometres

The two cameras were originally conceived as part of separate mission proposals, but ESA asked the teams to join forces in a single mission. The nearly unprecedented solution was to use a dichroic plate — a mirror that reflects visible wavelengths but is transparent to those in the infrared — to funnel light to both cameras at once.

Over time, Euclid will explore one-third of the full sky, always pointing away from the Milky Way’s disk and from the dusty plane of the Solar System so that it can peek deeper into extragalactic space.

Euclid (artist’s impression) will explore one-third of the sky from a point 1.5 million kilometres from Earth.Credit: ESA

Euclid is one of several upcoming observatories designed to take wide-field images and map the Universe in 3D. The 8.4-metre US Vera C. Rubin Observatory is finishing construction in Chile, and is scheduled to come online next year; China’s 2-metre Xuntian space telescope is scheduled to reach the Tiangong Space Station the following year; and NASA’s 2.4-metre Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope should launch in 2027.

“Each of these surveys will do very interesting things by themselves — and more interesting things together,” says cosmologist Jo Dunkley at Princeton University in New Jersey. Researchers will combine data to extract the large-scale properties of the Universe with greater precision.

Data pipelines

Data from Euclid’s two cameras will feed two types of analysis. Computer code will comb through the visible-light pictures to look for subtle distortions that typically squeeze the apparent shapes of galaxies by less than 1% in one direction or another. When mapped over large swathes of the sky, these distortions reveal the presence of enormous masses in the foreground, which curve space and bend the light coming from objects in the background — a phenomenon called gravitational lensing.

“This weak lensing effect is everywhere in the sky,” says Anthony Tyson, an astronomer at the University of California, Davis, who pioneered the technique beginning in the 1980s and then helped to spearhead the Vera Rubin Observatory.

This analysis will require researchers to combine Euclid’s black-and-white photos with colour images taken from ground-based observatories, especially Rubin. A galaxy’s colour correlates with its distance, so the extra information will help turn a 2D image into a 3D map.

The gravitational lensing will allow cosmologists to measure whether the dark-matter scaffolding is thin and dense or more puffed up, which in turn could provide clues to the nature of the elementary particles that constitute the dark matter, says Dunkley. It will also provide a way to measure the mass of subatomic particles called neutrinos, because the lighter they are, the farther they fly out of galaxies and the more they contribute to the puffing up.

The second analysis will explore the distribution of galaxies, looking for features that are remnants of waves in the featureless broth of matter that made up the primordial Universe. These ‘baryonic acoustic oscillations’ have been used before to track the rate of cosmic expansion throughout the Universe’s history, but Euclid will be able to push this type of study further back in time than ever before.

Euclid was originally scheduled to launch on a Russian Soyuz rocket from the European spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 put the mission in a “desperate” situation, says Giuseppe Racca, Euclid’s mission manager at ESA in Noordwijk, the Netherlands. “We were faced with possibility of putting the spacecraft in storage and launching in three to four years.” The team was relieved to find out that the spacecraft was compatible with a Falcon 9 launch.

The first results from Euclid are expected in 2025, but its full map will not be published until 2030.

The current favoured cosmological theory centres around dark energy and a particular type of dark matter made of heavy particles. The eventual outcome of Euclid and the other cosmology-mapping projects will be to put this theory to the ultimate test, says Rachel Mandelbaum, an astrophysicist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Once the analyses are done, the model will be “thoroughly stress tested”, she says.