A similar combination of weather patterns in 2019-2020 resulted in Australia’s devastating ‘black summer’ bushfires.Credit: Carla Gottgens/Bloomberg via Getty

The southern hemisphere is facing a summer of extremes, say scientists, as climate change amplifies the effects of natural climate variability. This comes in the wake of a summer in the northern hemisphere that saw extreme heatwaves across Europe, China and North America, setting new records for both daytime and night-time temperatures in some areas.

Andrew King, a climate scientist at the University of Melbourne, Australia, says that there is “a high chance of seeing record-high temperatures, at least on a global average, and seeing some particularly extreme events in some parts of the world”.

El Niño effects

Table of Contents

As 2023 draws to a close, meteorologists and climate scientists are predicting weather patterns that will lead to record-high land and sea surface temperatures. These include a strong El Niño in the Pacific Ocean, and a positive Indian Ocean Dipole.

“Those kinds of big drivers can have a big influence on drought and extremes across the southern hemisphere,” says Ailie Gallant, a climate scientist at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and chief investigator for the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes. In Australia, both of those phenomena tend to “cause significant drought conditions, particularly across the east of the country”.

During 2019 and 2020, the same combination of climatic drivers contributed to wildfires that burned for several months across more than 24 million hectares in eastern and southeastern Australia.

In eastern Africa, the combination of El Niño and a positive Indian Ocean Dipole is associated with wetter conditions than normal and an increased likelihood of extreme rainfall events and flooding. Above average rainfall is forecast for much of southern Africa in mid-to-late spring (October to December), followed by warm and dry conditions in the summer.

South Africa has experienced flooding in the spring of 2023.Credit: Rodger Bosch/AFP via Getty

In South America, El Niño has a more chequered effect. It brings wet conditions and flooding to some parts of the continent, particularly Peru and Ecuador, but hot, dry conditions to the Amazon and northeastern regions.

Leading up to 2023, the three consecutive years of El Niño’s counterpart, La Niña, brought relatively cool, wet conditions to eastern Australia, and led to record-breaking droughts and hot weather across the bottom half of South America. But the ‘triple dip’ La Niña has helped to mask global temperature increases associated with rising greenhouse-gas emissions and climate change, says King.

He says that, coupled with the El Niño conditions, the full effect of the changing climate is “emerging properly”.

Meanwhile, human activity continues to contribute to the levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Earth’s average 2023 temperature is now likely to reach 1.5 °C of warming

Climate scientist Danielle Verdon-Kidd at the University of Newcastle, Australia, says that heatwaves — one of the most deadly weather events — are a major concern for summer 2023. “We know that the conditions that we’ve got now …make it more likely that those sorts of systems will develop over summer,” she says

Summer of 2023 in the northern hemisphere saw unprecedented high temperatures in China, parts of Europe and North Africa, the worst bush-fire season on record in Canada and severe marine heatwaves in the Mediterranean. The large land masses in the northern hemisphere create areas of circulating warm, dry air known as heat domes, which block low-pressure systems that would otherwise bring cooler, wetter conditions.

In the southern hemisphere, heat domes are less of a concern. “We also have a big land mass in Australia,” Verdon-Kidd says, but the southern hemisphere has a much higher ocean-to-land ratio, “so our systems are different”.

On top of these converging phenomena, the Sun and atmospheric water vapour will influence the weather. King says that the Sun is approaching the peak of its 11-year cycle of activity, which could contribute a small but significant increase to global temperatures. Meanwhile, the eruption of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai underwater volcano in January 2022 has added to the amount of water vapour in the upper atmosphere, which is also expected to slightly increase global temperatures. The temperature changes are “hundredths of a degree to the global average, so nowhere near as important as climate change or even El Niño at the moment, but a small factor,” King says.

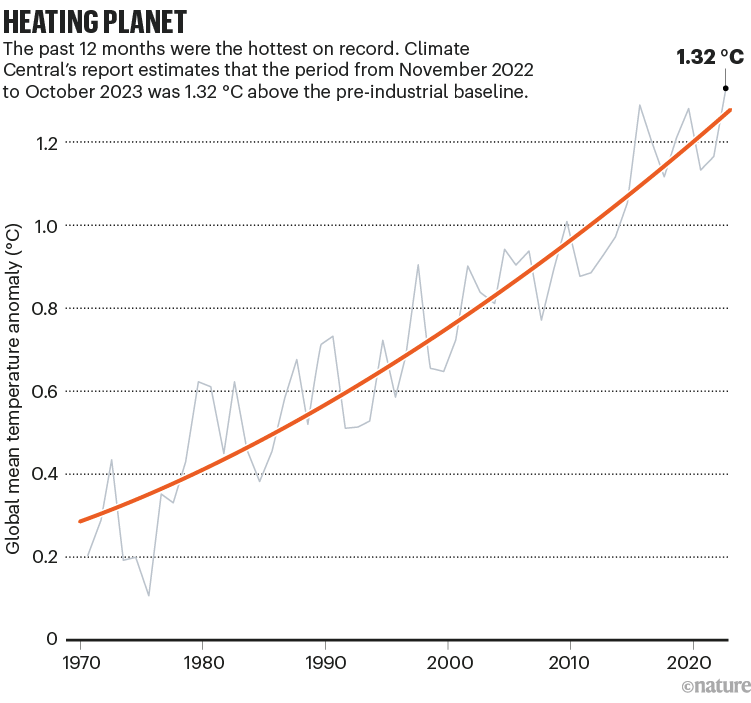

Source: Climate Central

Hot oceans

Oceans are also feeling the heat. Global average sea surface temperatures reached a record high in July this year, and some areas were more than 3 ºC warmer than usual. There were also record-low levels of sea ice around Antarctica during the winter, which could lead to a feedback loop, says Ariaan Purich, a climate scientist at Monash University. “Large areas of the Southern Ocean that would usually still be covered by sea ice in October aren’t,” she says. Instead of being reflected off white ice, incoming sunlight is more likely to be absorbed by the dark ocean surface. “Then this makes the surface warmer and it’s going to melt back more sea ice so we can have this positive feedback.”

As Antarctic ice melts, the darker water absorbs more sunlight, driving more melting.Credit: Sebnem Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty

Another meteorological element in the mix this summer is the Southern Annular Mode, also known as the Antarctic Oscillation, which describes the northward or southward shift of the belt of westerly winds that circles Antarctica.

In 2019, the Southern Annular Mode was in a strong negative phase. “What this meant was that across eastern Australia, there were a lot of very hot and dry winds blowing from the desert across to eastern Australia, and so this really exacerbated the bush-fire risk,” says Purich. A positive Southern Annular Mode is associated with greater rainfall across most of Australia and southern Africa but dry conditions for South America, New Zealand and Tasmania.

The Southern Annular Mode is currently in a positive state, but is forecast to return to neutral in the coming days, and “I’d say that we’re not expecting to have a very strong negative Southern Annular Mode this spring”, Purich says.

And, as hot as the summer could be, the worst might be yet to come. Atmospheric scientist David Karoly at the University of Melbourne, who was a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, says that the biggest impact of El Niño is likely to be felt in the summer of 2024–25. “We know that the impact on temperatures associated with El Niño happens the year after the event,” says Karoly.