If a coronavirus test (pictured) generates a positive result, the virus can be sequenced much more rapidly if sequencing is done in-country rather than abroad, a study of African nations reports.Credit: Dwayne Senior/Bloomberg/Getty

New SARS-CoV-2 variants arise and spread with great stealth, but that hasn’t stopped Africa’s genomic sleuths from spotting a host of these threats — and alerting the rest of the world. Now an analysis details how the rapid growth in Africa’s sequencing capacity has aided global SARS-CoV-2 surveillance1. It also reveals that most variants were imported into Africa more often than they were exported from the continent.

The study, published in Science, shows that “African scientists can work together to produce high-level science”, says co-author Tulio de Oliveira, a bioinformatician at Stellenbosch University in South Africa. “Before, it was almost the norm that African scientists would work with a northern partner to produce that kind of level of science.”

Homegrown talent

Table of Contents

In March 2020, during the early days of the pandemic, fewer than 15 of the 55 countries recognized by the African Union had the necessary infrastructure to sequence genomes. Now 39 have their own sequencing facilities. And what began as a small group of researchers in Africa meeting virtually has ballooned into a consortium involving more than 400 scientists and public-health officials from across the continent and beyond working together to track the spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants and monitor changes in the variants’ genomes.

As the consortium grew, so too did the number of sequenced genomes from Africa. By mid-2021, group members had sequenced more than 10,000 SARS-CoV-2 genomes collected on the continent2. By March this year, the count had reached 100,000.

The authors note that this marks a major milestone in African genomic surveillance. By comparison, only around 3,700 whole HIV genomes from Africa have been sequenced and publicly shared, although the virus has been circulating for decades.

These scientists traced a new coronavirus lineage to one office — through sewage

“This paper is incredible,” says Jeremy Kamil, a virologist at Louisiana State University in Shreveport. “The world needs to see more collaborations like this.”

Genomes from a total of 52 African countries have been deposited in GISAID, an online repository that is the world’s largest digital database of SARS-CoV-2 sequences. Some genomes were sequenced in the countries where they were sampled, some in other African countries and others in laboratories outside Africa.

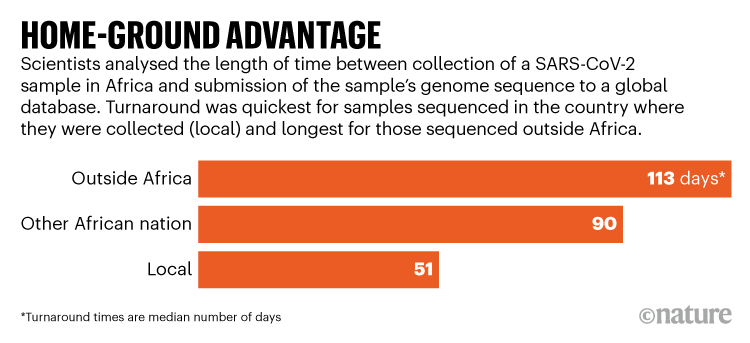

The researchers found that in-country sequencing offered a clear speed advantage. The median turnaround — the time between the collection of a specimen from an infected individual and the addition of a completed sequence to GISAID — for genomes sequenced locally was 51 days. Median turnaround was 90 days for samples sent to other African countries and 113 days for those sent to facilities elsewhere in the world (see ‘Home-ground advantage’).

Source: Ref. 1

These findings “jumped out at me right away”, says Kamil. Speed is crucial when it comes to fighting the virus, he says. If a variant such as Omicron is allowed to spread for even two or three extra weeks before it’s noticed, the world’s already-slow systems for updating vaccines will have even less time to catch up, Kamil adds.

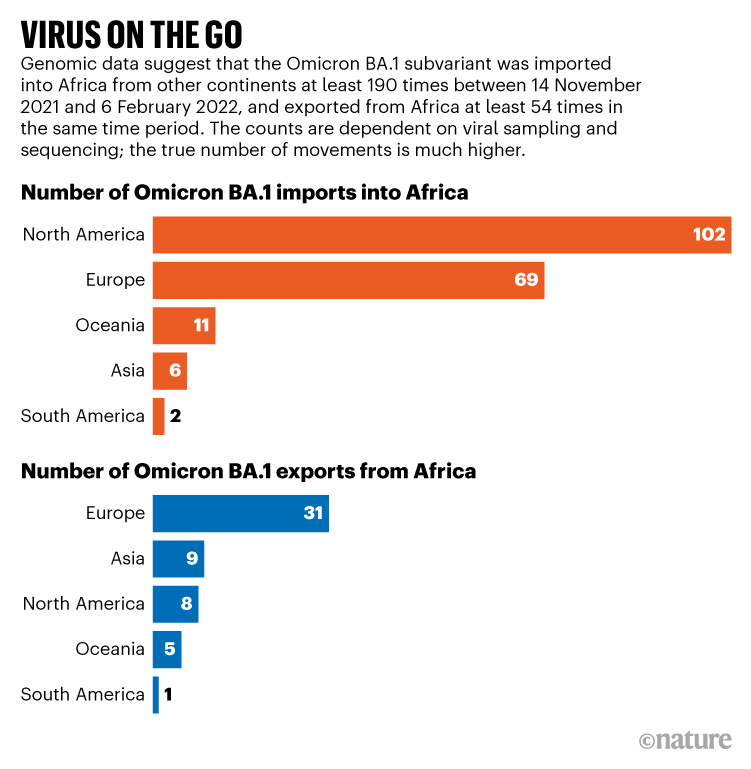

The collection of 100,000 SARS-CoV-2 genomes enabled de Oliveira and his colleagues to map when and where variants were introduced into Africa and how they had spread. The Omicron variant, for example, was first detected in South Africa in November 2021. The researchers found that although the Omicron subvariant BA.1 was exported from Africa at least 55 times — primarily to Europe and North America — it was imported into Africa at least 69 times from Europe and 102 times from North America (see ‘Virus on the go’). These import events brought the variant to African countries outside of the southern part of the continent, says study co-author Eduan Wilkinson, a bioinformatician at Stellenbosch University in South Africa.

Source: Ref. 1

Overall, the team’s analyses indicated that most SARS-CoV-2 variants were more often introduced into Africa from other parts of the world than the other way around. “The ironic part was that Africa was punished a few times from discovery of variants,” de Oliveira says. “But a great majority of the variants, including most of the introductions of Omicron, did not come from Africa.”

De Oliveira and his colleagues plan to adapt the existing sequencing infrastructure to monitor other infectious viruses and bacteria that are of concern in Africa, such as the tuberculosis bacterium, HIV and the Lassa and Ebola viruses. “We have a lot of pathogens to deal with,” de Oliveira says.