We are members of a social-science laboratory in Sydney, Australia, and collectively we research how social factors, such as gender or education, affect health and how people integrate digital technologies into their everyday lives. We have studied topics including smartphone use, women’s health and fitness practices and how people use smartwatches to track self-improvement metrics. Observing people in their everyday environments was an important part of our work. Being physically present helped us to understand people’s routines and relationships, and the social world around them.

And then, COVID happened. That meant no more face-to-face interviews or in-person research. Yet the need to understand people’s experiences — especially their health and relationship with the digital world — seemed more important than ever. We had to quickly redesign our methods and improvise, so we started experimenting with creative digital techniques to capture different voices and perspectives (see ‘Toolkit’).

Here are summaries of three such methods, alongside what we’ve learned about them so far.

Digital diaries

Table of Contents

As lockdown began, we noticed more people walking, cycling and repurposing outdoor spaces for leisure in our own neighbourhoods. We decided to investigate people’s improvised fitness practices during lockdown. We wanted to include a participant-led experience that reduced the real-time demands of doing live interviews on the videoconferencing platform Zoom, especially at a time when screen fatigue was rampant, that would allow us to capture meaningful moments outside an interview. We asked participants to start creating digital diaries so that they could tell their stories through a combination of photos and text, instead of relying on language alone.

Participants received a daily e-mail with a link to the ‘digital diary entry’ form. They were invited to upload a digital image related to their physical activity, and to tell a short story about what the photo meant to them. We were worried people might provide very short, descriptive answers. But participants uploaded a wide variety of images and shared thoughtful, emotional stories. These stories provided rich insights into the context and challenges of everyday life during the pandemic and highlighted the importance of physical activity for maintaining daily routines and providing a reprieve from the stressors of the pandemic. Our findings help us to understand the benefits of physical activity beyond health and aesthetics. These include providing a sense of ‘escape’ from the stresses of daily life during the pandemic, gaining a sense of control in times of uncertainty, creating daily routines and achieving a (sometimes fleeting) sense of calm. Digital photo diaries helped to bring these ideas to life in ways a virtual interview could not.

Zine making

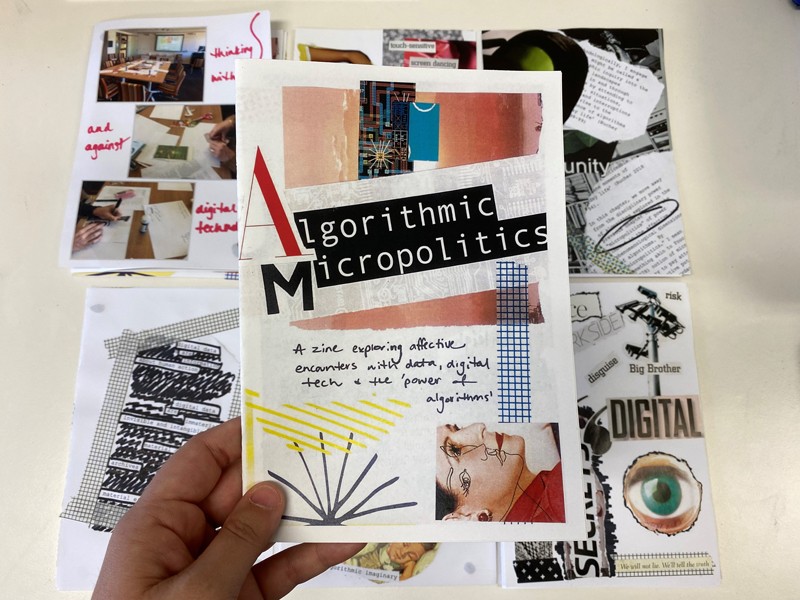

A second method in the series is ‘zine’ making. Zines (linguistically derived from ‘magazines’) are do-it-yourself publications of writing and visual art. People make these to share their creative work and circulate community information, much like an analogue form of blogging. Although zine workshops are often held in person, we have designed digital workshops that combine online and print creative processes.

Digital zine making works similarly to an online focus group. We aim to gather diverse perspectives on a given issue, for example, mental health and social media. So we bring a small group of participants together using Zoom to discuss the research topic. In addition, each person uses pens, paper and magazine scraps to create one or two pages in real time that represent their views. They then post or e-mail these to us, so we can compile a single zine from the workshop that ties their different perspectives together.

Standard focus groups can be dominated by one or two louder voices. People can also struggle to verbally articulate how they feel about complex issues. Zine making offers a creative process and a final product that distils people’s diverse views, and gives spaces to all voices. We analyse the discussion recording and content of the final product to get a nuanced sense of how people understand social issues.

YouTube

A third method in our series is analysing YouTube videos. We were analysing YouTube videos even before the pandemic because there are a huge range of communities active on the platform. As with many social-media platforms, people socialize through YouTube. This makes it a valuable site for content analysis and virtual observation.

Studying digital communities works in much the same way as in-person fieldwork — you need to be familiar with the community, be observant and take notes. First, we find relevant videos by searching keywords, and we identify leading creators by observing people’s uploads and engagement with their audience. Then, over many months, we watch hours of relevant videos to determine patterns in content and patterns of interaction — doing a qualitative analysis of what is in the actual videos, and the kinds of conversation people have in the comments sections. As with in-person observation, by studying online communities and their content, such as that on YouTube, we gain a rich understanding of how digital interactions change over time, and we learn how communities develop on platforms that are becoming more and more important in daily life.

These digital methods have helped us to continue our research throughout the pandemic. However, they have offered much more than a ‘next best’ option or temporary quick fix. By fully embracing creativity and digital alternatives, researchers across fields can gain rich insights and connections — which are especially important in these times of distancing. During the pandemic, collaboration and resource sharing provided much needed support for many of us.

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged.